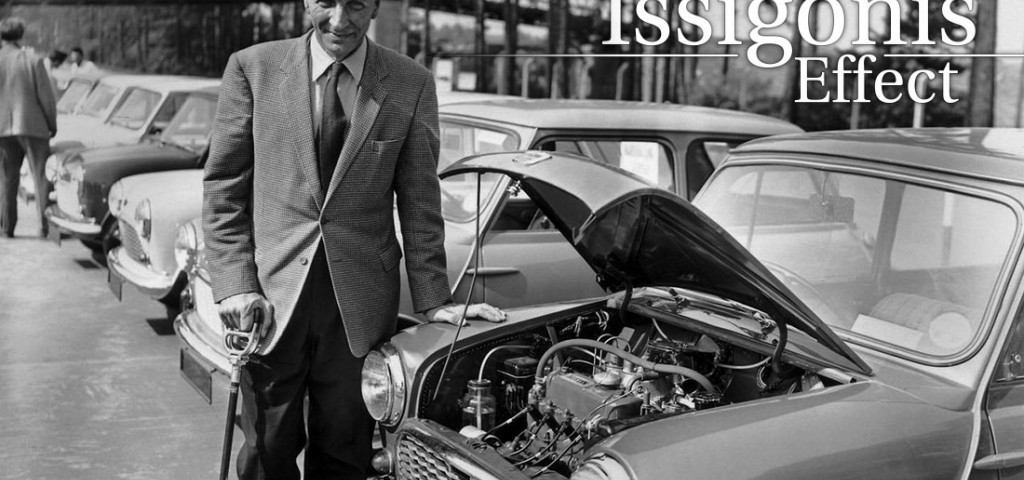

Without Alexander Arnold Constantine Issigonis, there’d be no Mini. The car’s chief engineer and designer—raised a subject of the Ottoman Empire by his Greek father and Bavarian mother—was widely known for penciling freehand engineering sketches. The stubborn eccentric designed the original Mini by eye and despised mathematics. “You must not mix function with fashion in a car,” he once said. “A car should take its shape entirely from the engineering that goes into it.”

Ongoing, even perpetual, celebration of “Alec” Issigonis is fitting in our view, if ironic. Although he changed small-car design forever and was 100 percent central to the Mini’s existence, Issigonis was pushed aside by the company that built his iconic machine not so long after he’d invented it, his trap-door demotion coming in 1968. Also, were he alive today, it’s fairly certain that Issigonis, the minimalist’s minimalist, would disapprove of the new version introduced by BMW. The outspoken engineer loved his cars small and unadorned, and today’s Mini is neither. Truth is, if Issigonis hadn’t shut up (he died in 1988 at age 82), they’d have had to shut him up.

Exiled from the Greek (now Turkish) city of Smyrna when Atatürk’s army invaded in 1922, Issigonis fled with his mother to Britain as a teenager. Although he would rise to a high place, becoming a Commander of the Order of the British Empire, roundly decorated by the Royal Society, Sir Alec knew what he wanted in his life. While he hoped, like Henry Ford, to move the working man ahead in the realm of creature comfort, Issigonis remained deeply, cantankerously spartan at heart; excess automotive size, weight, and frippery irritated the hell out of him. Strident asceticism would put him at loggerheads with marketing men, for on that point he was unapologetic. On the other hand, engineering complication in the search for simplicity didn’t scare him, either—but it troubled cost accountants. Thus, his key insights and greatest weaknesses as a corporate soldier were curiously intertwined.

Issigonis began training as a mechanical engineer in England with Humber in the 1930s, moving to Morris and then Alvis before returning in 1955 to the British Motor Corporation, which then owned Morris. It will be hard for many to believe today, but Britain was the world’s second-biggest motor-manufacturing nation through the 1950s and into the 1960s. BMC, which represented the 1952 merger between William Morris’s Nuffield Organization and the late Herbert Austin’s eponymously named firm, was one of the largest car companies in the world. One reason was the Morris Minor, an excellent small car in its day (1948–1971) and a commercial home run; Issigonis had laid it out during his first stint at Morris.

At the behest of Leonard Lord, the Austin chairman ascendant in the postmerger reorganization, Issigonis was summoned back to BMC and quickly tasked. Horrified by the incursions of German and Italian microcars in the days following the 1956 Suez Crisis and the resultant fuel shortages, Lord challenged his new chief engineer to come up with a competitor. “God damn these bloody awful bubble cars,” the celebrated British motoring writer L. J. K. Setright quoted Lord as instructing Issigonis. “We must drive them out of the streets by designing a proper miniature car.”

Issigonis had long pondered the space-utilization advantages of front-wheel drive and quickly delivered an advanced concept—notwithstanding that in 1957 and 1958, the period of the Mini’s gestation, the computer was still an oddity and the slide rule the primary tool of the engineer’s trade. With a team of eight at Austin headquarters in Longbridge, England, Issigonis and his freehand drawings guided the building of running prototypes in a scant seven months. In double time, he’d worked out the particulars of a small, two-box car whose engine was turned sideways and placed above its transmission (with which, fatefully, it shared lubrication). Wheels, small and cleverly suspended by rubber (and later fluid), would be pushed to the corners.

The rest of the story is the stuff of lore. Even though it would rarely earn its makers much—if any—money, the Mini would become a classless cultural icon and prove to be so popular that its amazing voyage as a salable commodity comprised four full decades with ports of call in two others. A work of packaging genius, it allowed a remarkable 80 percent of its tiny footprint (ten feet) to be devoted to passengers and their things. With out-of-the-box thinking about what happens inside the box, the Mini established principles of vehicle architecture that inform car design today.

That first car also suggested the layout of several Mini variants (wagon, pickup, van, and beach buggy), plus many larger corporate relations and a host of imitators. Leaving service in 2000, it spawned BMW’s first Mini tribute of 2001, the opening salvo in what has been a committed effort to grow a more encompassing brand out of the most admired name in very small cars.

Impressions from the Road

Ultimately, other manufacturers would learn to profit from Issigonis’s advanced design strategies where BMC failed, the cost and the complexity of its new cars for many years helping to drag the company—troubled in many other ways, it’s only fair to note—down. What is it they say about why you want to be second to the market with new technology? Thanks to Alec Issigonis, BMC was there first, and to celebrate his achievements, explore with me the Issigonis Effect in action in two of his creations.

First up, the original. Flatbedded my way from the corporate collection came what BMW terms a “Classic Mini.” For some reason, that conjured in my mind a 1959 Austin Se7en or Morris Mini-Minor, as they were also first known. But what showed up was a luxed-up 2000 Classic Cooper edition, one of the very last old-style Minis built. Roll-up windows and a full-width dashboard meant it lacked the early cars’ solitary, centrally mounted speedometer pod, sliding door glass, and capacious door bins, of which Issigonis was particularly proud. It also came with twelve-inch wheels, huge next to the ten-inchers that graced earlier cars, plus—gack!—an airbag, a radio/cassette player, and air-conditioning, all obviously non-options in the car’s formative years.

Along with the original’s microscopic dimensions, even final editions of the Mini had bolt-upright seating and steering wheels canted as if for bus drivers. Issigonis liked to quip that he intended to ensure that drivers remained alert at all times. And, like its predecessors, the last old Mini was plenty fun to drive. Thanks to a wide track and a relatively long wheelbase, as well as a low center of gravity and a clever suspension, the Mini would deliver, its inventor posited, 70 percent more roadholding than conventional small cars of its era. In time, such tenacious grip would lead to the Mini’s many competition successes (Monte Carlo Rally overall victories in 1964, ’65, and ’67, for instance) and a general reputation for cornering prowess, as well no doubt as an accident or two borne of overexuberance.

While it boasted old design, this build-out special nonetheless possessed a sense of modernity, and its urge (zero to 60 mph in thirteen seconds) a testament to an injected, 1275-cc A-series engine with 63 hp. At roughly 1520 pounds, this Mini Cooper was heavier than early Minis. But it went, and even with but four gears, carefully selected ratios meant motoring at highway speeds without trouble or much engine roar at all. That was a surprise.

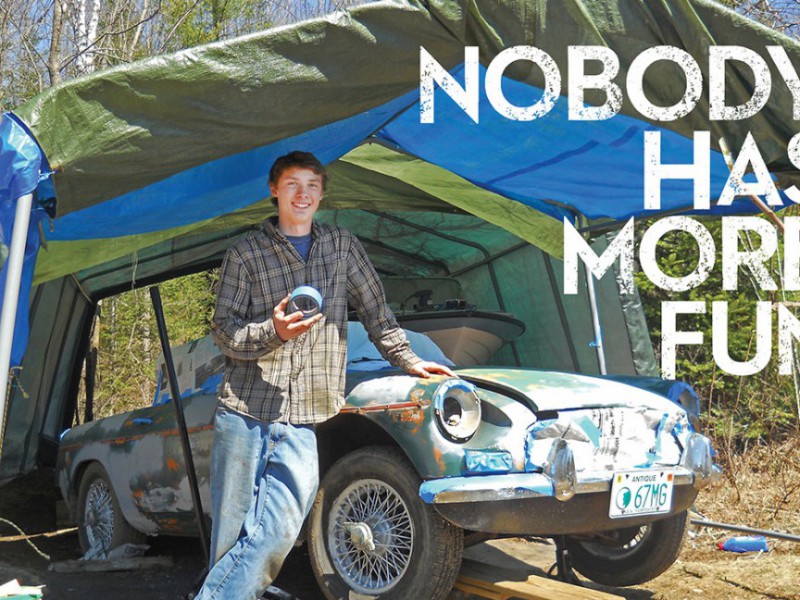

From my Garage: the MG 1100

An old BMC ad said of the Mini, “[T]he bigness is in the proper place—inside!” True enough, but nowhere was Issigonis’s space-efficient thinking more evident than in the Mini’s bigger brother, launched in 1962 and code-named ADO16. A not very large but incredibly spacious evolution of the concept, its feasibility was enhanced by an emergency last-minute revision to the Mini’s build spec—separate subframes.

ADO16 distinguished itself in every one of the dozens of iterations in which it appeared—two-door, four-door, wagon; MG (the example I own), Morris, Austin, Wolseley, Riley, and Vanden Plas—by actually having room for four or even five adults and their luggage. Such vast space in a car so short, mated to 35-mpg fuel economy and ample potential for driver amusement, is not an achievement to sneeze at. Its twelve-inch wheels might not be fashion correct anymore, but along with a uniquely compact “Hydrolastic” fluid suspension penned by Issigonis’s eccentric associate, Alex Moulton, they help deliver a commendably smooth ride and a low-riding minimum of body roll, although the faintest pitching can be detected on rougher surfaces owing to the movement of fluid between its interconnected front and rear spheres.

As a sporting, upmarket version of this unashamedly badge-engineered model, the twin-carb, 55-hp (twenty-second 0-to-60-mph time) MG is handsomely trimmed in red vinyl but resolutely spare even so; a strip-band speedometer, fuel and temperature gauges, and a quartet of toggle switches are all that adorn a thin, car-width dash covered in ersatz wood. But with its solid construction and airy accommodation, the MG is a pleasant, even luxurious, car in all respects save one, living proof that the British industry did not go down without moments of incredible inspiration. That one demerit: it’s kinda screamy on the highway.

Purchased new in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, the 1966 1100 you see here was intended to be a high-school graduation gift for a businessman’s daughter, bought in the hope that she would restore Christian virtue to her life. When she proceeded to flunk out of junior college and then get pregnant, her moralizing dad yanked the keys, whereupon the car began twenty-five years of stationary repose in a corner of his factory. After he passed away in the early 1990s, it bounced between collectors. Seven years ago, one of them bumped into me. At the time, this car had 850 original miles. Today it has but 4,200.

Britain’s best-selling car for most of its 1962–1974 life span, ADO16 was quite successful in the Commonwealth. But somehow it never set America on fire, selling slowly in MG garb and later, with more fanfare and hence more disappointment when it bombed, as the Austin America. It was the last of Issigonis’s technologically nouvelle offerings to grace our soil.

I’m not sure because there is no tach, but it sounds like this 1100 approaches 9000 rpm at 65 mph in top gear. Badly blinkered (and wearing earplugs), British industry ignored the 1960s highway reality at its peril. That said, this is indeed one of my favorite cars.

By Jamie Kitman

Jamie Kitman has written for Automobile Magazine, CAR, Top Gear, GQ, New York Times, Harper’s, Men’s Journal and The Nation. Growing up in Leonia, N.J., one-time home of BMC, he has had a lifelong affection for British cars, which may explain a motor house that currently contains no less than a dozen British classics and oddities.

'The Issigonis Effect' has no comments

Be the first to comment this post!