While the Triumph name and competition reputation predate WWII, Americans are most familiar with the robust roadsters and Triumph-badged Standard saloons (sedans) built after the war by the newly formed Standard Triumph Motor Company. Director Sir John Black combined the solid and dependable Standard with the sporty, almost hand-crafted, Triumph sportsters into his own vision of the future—much like William Morris (later Lord Nuffield) had done by combining Morris, Wolseley, Riley, and MG into the multi-marque Nuffield Organization (and GM had done in the States).

Postwar, a few Triumphs were shipped here alongside MG-TCs and Austin A-40s to help rebuild Great Britain. (The national “Export or Die” program actually made it easier to buy an Austin in New York than in London!)

These were the amazing swooping Triumph 1800/2000 roadsters with “dickey seats” and “razor edge” saloons, the first to use the Standard wet-liner four that was fitted to the senior Triumphs until the last TR4. To those of us who discovered British cars as children of the 1950s, the Triumph TR2/TR3 always seemed to be one of the major players on the American sportscar scene. Dinky Toys introduced a series of sportscars that included a TR2 along with an MG-TF, an XK120, and a Sunbeam Alpine. Hubley did a 1/25th-scale TR3 in both kit and built-up form, and the 1/32nd-scale imported slot race sets also featured TR3s.

While not the Masterpiece Theater window-into-prewar-Britain like the dainty MGs and archaic Singers (or the sleek and swoopy “Hollywood” cars like the Jags and Riley Dropheads), the TR3 made a name among enthusiasts as a careful blend of old and new with a modern overlay and impressive performance: designed for people who drove their special cars rather than wore them. The fit and finish was well above the entry-level sportscars of the day, and these TRs were powerful enough to hold their own—even among V-8-powered American cars.

The TR2 was introduced at the London Motor Show in 1953. The production TR2s, sold as 1954 models, quickly backed up their modern sporty look by taking First, Second, and Fifth Places in the 1954 RAC Rally and blasting out a 125mph run down the Jabbeke highway in Belgium.

The earliest of these cars have doors that go all of the way down to the bottom of the car. Today these are called “long door” models. Once TR2s were delivered to the States, their doors’ length was too low for our curbs, and the factory was asked to raise the bottom doorline for curb clearance. The result not only made entry easier but stiffened the body structure to an additional advantage.

The TR3 was introduced in late 1955 with a revised grille and more horsepower. In late 1957, the updated TR3A was brought to America. It featured a wider grille for better cooling, external door and bootlid handles, and an optional hardtop model.

The next-generation TR4, with its new Michelotti-designed body, was first produced for export in July ’61. American importers were unsure about how the new styling would be accepted, as the TR3 was still as popular as ever, so they requested Triumph to continue building the TR3. These cars, called TR3Bs, placed the latest TR4 mechanicals in the original body style. This car stayed in production until 1963.

Good Points

Fun and robust with plenty of punch for a mid-priced roadster, TR2s and TR3s are as popular as ever today. Parts are relatively easy to obtain, and the car has few mechanical surprises. Via the Internet, we asked Triumph owners why they bought Triumphs:

ESTIMATED PRICES

Model Project Running Good Excellent Concours

TR2/TR3 $6,000 $8,000 $13,000 $18,000 $20,000

TR3A/TR3B $6,000 $8,000 $14,000 $20,000 $23,000

Harris Palmer says, “The design attracted me. To me, it appeared tough, tougher than an MGA or Healey 3000. Whenever I saw a print ad for the car, I would dream of owning one. Loved that low-cut door.” John Lipsky of Woodbridge, Connecticut, concurs: “Firstly, it is the classic lines of the car. No matter when I look at it, it attracts me by its timeless design.”

Marty Lodawer of the Triumph Register of Southern California says, “They have to be the easiest cars in the world to work on—everything is accessible and simply engineered to come apart easily. Components are designed to be rebuilt rather than replaced; these are cars that can be repaired and maintained by a relative amateur in a home garage.”

Bad Points

Justin Paxton warns, “Cooling in general does not do well in traffic on hot days in Southern California, and the car can overheat if driven hard. The top-down ride tends to beat up the occupants with wind buffeting at sustained freeway speeds. Cornering: The car tends to body-roll on sharper turns without installing a swaybar. The side curtains were behind the times, even in 1959, and are particularly hard to store in the car. The top is way too hard to put up and stretch the canvas over and attach, especially in cold weather. The overdrive mechanism is finicky, difficult to adjust, and the solenoid often fails and is expensive to replace. The muffler is too close to the interior and without insulation can burn the passenger’s leg. The electrics, with basically two fuses protecting the entire car, are woefully inadequate.”

Harris Palmer adds, “In winter weather (below about 25 degrees), the heater is useless. The valves seem to be noisy all the time and I’m constantly adjusting them. Luckily, it’s easy to do.”

“My main criticism,” says Glenn Coughenour of Bryn Mawr, PA, “is the mediocre rust protection and paint from the factory. Also, a lot of things are bolted together that others would have welded. This leads to rattles and panel-fit issues, but it does make rebuilding one a lot easier.”

Aside from the obvious rust and poorly done body-structure repairs, Jeff (Cosmo) Kramer from Royalton, NY, concludes, “The buyer should know what they want to use the car for, then decide how much they want to put into it. You can’t be afraid to try to work on it—read the Workshop Manual and try to understand it. Otherwise, you will need to pay a professional to do a GOOD job. A new owner should understand that a well-maintained Triumph is a must for dependability—just like any other car made in that same time period.”

About Values

The biggest problem these days is finding a good TR for sale. The few cars we inspected through various classifieds were either basket cases that required twice their completed value to restore or overpriced, mediocre restorations at “classic car” dealerships. Marty Lodawer explained, “The mid-line runners are not around anymore, and the truly nice cars are not worth enough yet for people to sell. When you spend over $25,000 restoring a car, it is hard to let it go for $18,000, so you put it away for a while.”

Even though some value guides break down these cars by year, the prices are pretty much the same for all TR2s and TR3s. They have to be judged upon quality and originality. Some people will opt for the earlier cars because of rarity and history, while others will pay a premium for the latest model available because these generally contain better and more modern mechanicals.

While some modifications—like engine swaps and body mod—will detract from values, upgrades like better brakes, modern all-synchro 5-speed gearboxes, and electronic ignitions can add value to the right buyer. Wire wheels are a matter of taste, not value, yet factory accessories like the removable hardtop and fender skirts (spats) can add thousands.

Dave MacKay, from Mississauga, Ontario, Canada, adds this final thought: “The most important thing is to connect with a good local Triumph club, and to join the triumphs@autox.team.net Internet e-mail list. Both are great sources of information and camaraderie.”

British Value Guide—Triumph TR2/TR3

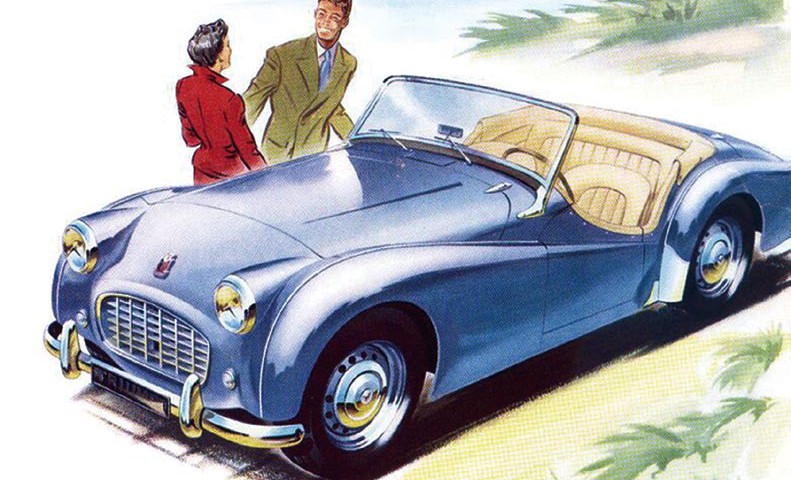

“The illustration shows the spacious accommodation, unusual in a car of this type, the paneling enclosing the spare wheel and the substantial over-rider. A suit case, specially designed to fit in the luggage trunk, is available as an extra.”

“Isn’t that a tractor engine?”

Heard that one before? In the case of the Standard/Triumph 1800/2000 four, it’s true but with a twist. The engine was first engineered to be fitted in the big (by British standards) Vanguard saloon and estate (station wagon), cars that featured a sort of Nash/Hudson/Packard overturned-bathtub approach to styling. A sporting version of this engine was implanted in the first classic-looking postwar Triumph roadsters and “razor-edge” saloons.

The story goes that a large portion of postwar financing came through Harry Ferguson, the tractor maker, who contracted to have Standard/Triumph assemble his light tractors at their out-of-use facility at Banner Lane, just outside Coventry. While the first tractors off the line used outsourced Continental engines, the Standard/Triumph two-liter four was re-engineered for tractor, marine, and industrial applications.

—Rick Feibusch

'British Value Guide: Triumph TR2/TR3' has no comments

Be the first to comment this post!