by Russ Sharples submitted by Mitchel L. Friedman

I’ve seen a lot of burned and melted wires in little British cars in my time. This is not surprising, considering that most of these cars were built with just two fuses. When a short circuit occurs in an unfused wire, the wire rapidly heats up all along its length. As it gets hot, the insulation first softens and droops, but there is no smoke yet.

Once it gets hot enough, the insulation burns, turning black and releasing the famous Lucas smoke. Up to the point of smoke, the wire can be saved, though once the insulation chars, it is difficult to avoid replacing the wire. I’ve seen smoke a few times when working on cars, but have always managed to save the wires.

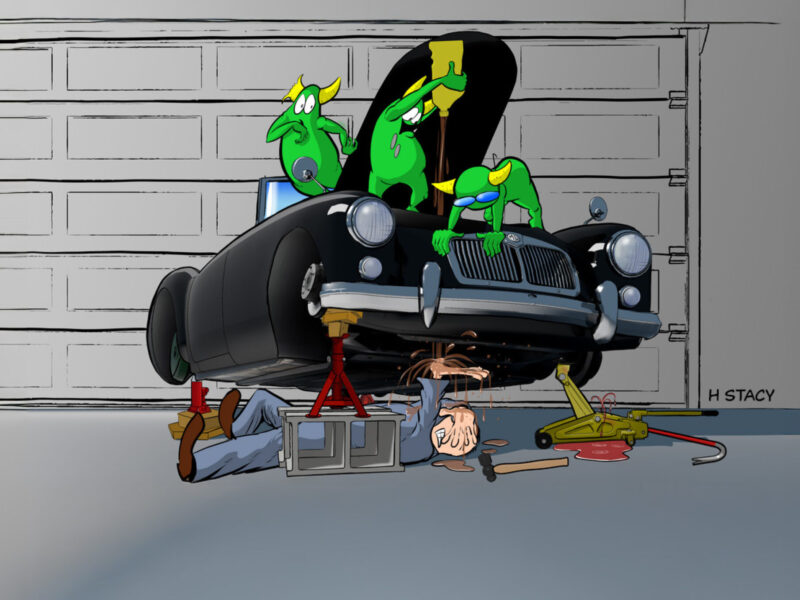

However, back in January, I had a unique experience—an actual full-blown fire!

My friend, Mitch Friedman, had just gotten his ’72 MGB back from the body shop following an accident that damaged the driver-side fender and door. Mitch couldn’t get the car started at the body shop due to the fuel pump not running, so it had been delivered home by tow truck. I was there to check out the pump’s wiring.

As it turned out, that morning, the pump fired right up—no trouble found. With that problem magically fixed, we set about checking out other things: coil—check, turn signals—check, wipers—no go, washer—no go, and so on.

When we got to the headlights, Mitch flipped on the switch. They work, and he then flicked them to high beams, which turned on just fine. As the high beams came on, I was under the hood checking the fuse for the wipers, and I see a curl, a singular wisp, of smoke coming up from the grill area.

“SMOKE! Turn it off!” I yell. Mitch cuts the lights, and the smoke stops.

I went to investigate the source, and it turned out to be pretty obvious—the body shop had connected the black ground wire from the side marker light to the bullet junction for the blue/white wires for the high beam lights. The smoke had come from the ground wire. It was not damaged, but we left it connected as we inspected the rest of the wires.

Then I looked up and saw a thick plume of smoke coming from the steering wheel binnacle.

“SMOKE!” I yelled again and ran to the interior of the car.

We had to disconnect the battery, but the car had no battery cutoff switch, and the terminals were tightened onto the battery. We couldn’t find the right-sized wrench to loosen them. Mitch goes looking for the wrench, and I check the steering column again. Smoke is pouring from the hole for the left stalk, which controls the turn signals and the high beam/low beam switch.

Mitch found the wrench, and we got the battery disconnected, but when we looked back at the steering column, there were now flames coming from the hole.

“FIRE EXTINGUISHER!”

I started blowing into the hole, which did nothing but irritate the flames. Mitch came back with an extinguisher; he aimed at the steering column and pulled the trigger. It put out the fire in one quick burst and covered the entire dash with yellow powder.

Luckily, the new interior Mitch had bought for the car was still safely in boxes. The work of cleaning the dry chemical agent from the dash instruments and switches was significant, but we got it done that morning—that dust goes everywhere.

Praise to Mitch for:

1) having a fire extinguisher,

2) knowing where it was, and

3) knowing how to use it!

Removing the binnacle revealed the culprit and allowed us to start figuring out what happened. It was as if someone had hit the lighting switch with a blow torch. The switch itself was melted, and the insulation on the wires in the vicinity of the switch was gone. However, the wires elsewhere were fine—there was no evidence that a short circuit had occurred that caused the fire.

The wires where they emerge from the harness sheath near the switch and at the other end at the connector were fine, with no evidence of melting or burning to indicate that the wires overheated. If the short circuit in the wiring harness up front had been the source of the fire, then we would see damage all along the wire. Instead, the heaviest damage was the switch itself. To me, this meant that the fire actually started in the switch and burned it up, scorching the wires simply because they were above it.

So what could cause the switch to catch fire?

The car was just back from the body shop where they would have been sanding paint and the plastic body filler. It is possible that this dust had gotten into the switch contacts.

This car had a flash-to-pass feature on the stalk: pull it towards you, and it flashes the high beams. This feature worked even when the lights were off—it is powered by the same circuit that powers the interior lights—so it had power even when the headlight switch was off. Mitch had flicked this flash-to-pass switch while testing the lights.

I conjectured that this started a chain reaction where some current was flowing through those switch contacts, and the dust in the contacts created resistance, which resulted in heat. This heat burned up the dust material and fused the contacts together so that when Mitch released the flash-to-pass switch—the power continued to flow.

While we examined the wiring in the front of the car, I left the ground wire connected to the high beam junction to show Mitch and document it with a picture, but this meant that with the flash-to-pass switch fused, the current was continuing to flow.

The resistance in the switch was enough to prevent the lights from lighting and the black wire from smoking, but the current was sufficient to create the heat to set fire to the material in the switch and eventually the switch itself.

Once it started to burn, it didn’t matter that we had cut power to it; at that point, the plastic was burning.

While new replacements for the binnacle are not available, we were able to find one on eBay. Luckily, new replacements for the switch were available from Moss Motors. We ordered the replacement parts, and I fully disassembled the steering column and cleaned all the remaining switches.

The lighting/turn signal switch is unique in that it has a completely exposed design, allowing dust to easily get inside of it. The other switches are at least somewhat sealed or completely sealed.

We installed a battery cutoff switch and all the new parts. After carefully inspecting all the wiring junctions, we connected the battery and started testing things. Everything passed; the wiper switch hadn’t worked before, but cleaning it had fixed that.

The car is back together with its new interior and on the road. There’s probably still extinguisher dust in the crevices of the dash, but that is now part of the car’s history.

Hopefully, 30 years from now, the car will get some attention from a new owner who will ask themselves, “Why is there all this dust in the dash?” and they will never know about the car’s harrowing experience with fire in the hole!

'Fire in the Hole' has no comments

Be the first to comment this post!