By Paul Richardson

My father, Ken Richardson, who was competition manager of Standard Triumph, organized an attempt on World Endurance Records with a TR3 at the Monza circuit in Italy—and I was to witness it.

Ken decided to combine the record attempt with our family holiday on the Italian coast near Pisa. When the news was announced, I remember my two younger brothers and I being totally elated at the prospect of spending a week at a race circuit followed by a holiday, and my dear mother Maisie was also looking forward to it.

We arrived at the Monza circuit on a hot summer’s day towards the last week of July 1959. After winding our way round the small service roads inside the circuit, the Richardson family took up residence in a spacious bungalow owned by the Shell petrol company, which was conveniently placed only a few hundred yards from the pit area. I remember my mother noticing a large fridge packed full of Coca Cola, and there was some freshly delivered Italian ice cream on hand.

Ken devised the record attempt as a follow on from the 100-hour endurance type tests he was involved with on experimental aircraft engines throughout the second World War. He was convinced that a TR could take several world endurance records at over 100 mph (which was why he went ahead in the first place), but his real aim was to attempt 100 hours at over 100 mph. For further publicity, he decided to use amateur drivers to prove that the man in the street could take a world record in a TR. Thus, he recruited a team of eight undergraduates from Cambridge University who were also members of the University Motor Club.

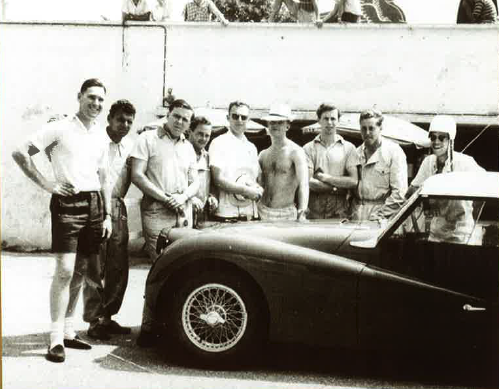

Ken Richardson making final carb adjustment before the start of the record run. “Dunlop Mac” on right, Tom McCulloch on left.

Two days before the start of the record attempt, everyone connected with it began to arrive at the circuit, including the star of the show—a pristine TR3 finished in red with a white hard top. The car was unloaded off the transporter and the build up to the record attempt began. The three competition mechanics that prepared the car and pit crewed were Ben Warwick (competition department foreman), the late and very dear George Hylands, and Tom McCulloch. I’m delighted to report that I’m still in regular contact with Ben and Tom and often talk over old times with them. Another member of the team was David McDonald, ever known as “Dunlop Mac.” Mac was a tire expert with Dunlop, who had been involved in world record attempts with the company, including land speed records, for some 40 years. He was a most wonderful guy and wrote a book of his life story called “Fifty Years with the Speed Kings,” which included the Monza Run.

My father had hired the Monza circuit for a week, and I remember the management and officials at the circuit treated the Triumph team extremely well. It was not long after we’d settled in when Seppe Bacciagaluppi arrived to welcome us. He was in charge of the circuit and was a friend of Ken’s (Ken spent a three-month stint at the circuit testing the V16 BRM grand prix car circa 1951).

Seppe and his wife made us most welcome. His house was inside the circuit and I remember he very kindly let us use his private swimming pool, which turned out to be a blessing for everyone as it was extremely hot at Monza that week.

It was the 25th of July when the record attempt began, and nervous tension built as the car took up its position in the pit lane prior to the start of the run. The mechanics made last-minute checks, including a sound test on the two-way radio. Yes, the TR had a two-way radio fitted for pit-to-car communication—was this another Triumph first, I wonder? The installation was quite a cumbersome affair, as the large unit took up most of the space in the passenger footwell. A final check on the spares in the boot (trunk) and the lid was closed (for the record run, all the spares that might be needed for any serviceable mechanical problems had to be carried in the car). The officials took up position in their timing box at the end of the pit area, and as the TR3 accelerated away on its proposed journey of 10,000 miles at over 100 mph, the tension lifted and the team began the business of record breaking.

The four days and nights that followed were an awe-inspiring experience for me because my brothers Ian and Charles and I were allowed in the pits throughout the run, albeit under strict instructions from my father to stay out of the way during pit stops. As a car-mad young boy of only some 15 years of age, I naturally felt part of the team and wanted to do my part, so I made tea, wrung out and cleaned wash leathers for screen cleaning, kept the pit tidy, and generally tried to impress everyone in the team.

The TR ran like a clock, and after I remained in the pits for most of the night on the first day with dad and the lads, I succumbed to the onslaught of lack of sleep. As dawn broke on another boiling hot day, my eyes began to close and my head nodded as I tried fight it off. Apparently, I fell asleep on a pile of tires clutching a wash leather. I awoke in our bungalow some nine hours later, somewhat indignant to find out that I’d been carried back asleep by Dunlop Mac and put to bed. The first world record for twenty-four hours at over 100 mph had also been broken—and I’d missed it.

The TR3 motored on for lap after lap of the banked circuit with that reassuring exhaust note that typifies a side screen TR at full chat. Pit stops for fuel and driver changes were just routine, and I suppose there must have been in the region of 50 such stops throughout the record run. My father, as was his way, was present at the vast majority of those pit stops, and his capacity to work without sleep, whilst remaining fully alert, was a trait often talked about by his mechanics.

It was on the last day of the run in the 96th hour when disaster struck. As the TR approached the pits flat out on the main straight, the engine suddenly revved higher followed by a heart-sinking clunk. The engine had blown. Apparently, due to the onset of a bout of tiredness, the driver at the time momentarily lost concentration and mistakenly down-changed from overdrive top when the car was at full speed. After traveling for 96 hours at full chat, this proved enough to blow the TR engine and the record run was over—only four hours away from the final goal of 100 hours.

The driver, bitterly disappointed, immediately admitted his lapse of concentration to my father. Ken, who admired honesty in such circumstances, took his personal disappointment well, and if I remember correctly, the driver became a member of Ken’s timing crew with the Le Mans “Twin cams.”

To miss the 100-hour final goal was heartbreaking for the whole team, but this was motor sport, and there were no recriminations as the efforts of everyone involved were amply rewarded. Eventually, smiles broke out when it was confirmed by the officials that the TR3 had already broken eight Class E world endurance records at over 100 mph.

I was to meet one of the drivers on that record attempt some 30 years later in the most bizarre of circumstances. Circa 1989, I had organized a high-level corporate event for a major engine manufacturer in the U.K. at the Henley Rowing Regatta. There were about 60 heads of companies present as guests, and the directors of the host company made it plain to me that nothing must go wrong. They were especially concerned that their main guest, a gentleman called Mr. “G. Boxall,” who was the chief executive of the huge Vickers Engineering company (this company made tanks, among other armaments), should receive 10-star treatment.

The name “Boxall” rang a loud bell with me, and eventually the penny dropped. Could Mr. Boxall be the same Gerry Boxall who was one of the TR drivers at Monza over a quarter of a century ago? When Gerry arrived, I immediately recognized him, and after introducing myself I said, “I think we’ve aged a bit since the Triumph Monza run in 1959, Gerry.” He looked at me totally amazed, and after my explanation of my presence at Monza as a 15-year-old boy, he burst into laughter and said, “My dear boy—let’s go and have a pint.”

We had several pints and a most delightful reunion. The sales director of the host company, who was suitably impressed with my first name relationship with his top guest, increased the volume of my working contract thereafter. It’s not always what you know, is it?

'The Monza Run' have 3 comments

May 16, 2017 @ 12:18 pm Mike Frazzell

I love the Monza record attempt story!! I bought my ’59 TR3 in June of 1960 and still have it. I was never aware of this attempt at Monza and found it delightful.

As you know, Paul Richardson writes stories of TR history in most issues of the VTR magazine and knows more than anyone about that history. Thanks for your articles .

As an aside, your Ken Hyndsman helped me greatly last Summer with a problem I had.

May 17, 2017 @ 9:45 am KEn Mohlman

Great story

May 17, 2017 @ 10:52 am Jonathan Wright

Great article! It has given me a clear vision of the little British TR lapping the big Italian Monza track. I’ve driven my TR, which I’ve had for nearly fifty years, over many a fast mile, although we don’t see 100 as often as we used to. If Triumphs were still made, the world would be a happier place.