By Graham Robson

A twin-cam Le Mans engine, independent rear suspension for the Spitfire, modular body shells for the Herald, Spitfires which raced at Le Mans, front-wheel-drive for the Triumph 1300, fuel injection for the TR5, and an all-new overhead-cam engine for the Dolomite—all were innovations, and all were completed between 1956 and 1968, while Harry Webster was Standard-Triumph’s technical chief.

Webster, Stanley Markland (of Leyland) and the Triumph Vitesse.

Webster, Stanley Markland (of Leyland) and the Triumph Vitesse.

New Triumph models poured on to the market at this time—Heralds, TR4s, Spitfires, GT6s, 2000s, Vitesses, and 1300s—so is it any wonder that I rate Harry as one of the great innovators? Here was a man whose team designed semi-trailing arm rear suspension years before BMW thought of it, a lift-off ‘Targa’ roof for the TR4 ahead of Porsche, and put wind-up windows and face level ventilation into sports cars well before BMC followed suit.

After British Leyland was formed, Lord Stokes immediately moved Webster to Longbridge to rescue Austin-Morris engineering. Charles Griffin, Alec Issigonis’s deputy, who later served under Webster, once told me, “He was totally different from Alec, much more practical, and much more hands-on. We got on well together.”

Much of this was backed by Leyland’s money (they rescued Standard-Triumph in 1961), but all the new thinking—in chassis, suspensions, engines and styles—was done against the clock in Coventry, inside very tight financial constraints.

Webster deserves much credit for this, though the backing of managing director Alick Dick and, later, Donald Stokes, made it all possible. Without Harry, and his styling associate, Giovanni Michelotti, there might have been no flair, enterprise, or technical excitement. It was all achieved by a small engineering team, using the minimum of equipment. Enthusiasm, vision and guts brought it about, not money.

Yet in the 1960s Webster’s enterprise was often ignored. Alec Issigonis and Colin Chapman were fashionable and making all the headlines—Issigonis the ‘one trick pony’ who never improved on the Mini, and Chapman the dictator who inspired great Lotus race cars, but unreliable road-going models.

Webster’s team transformed Standard-Triumph’s image. Until 1956, the dour Ted Grinham was the technical chief, and the cars reflected his character. With Webster, the engineers began to have some fun. Along with general manager Martin Tustin, Webster—the man whose tiny chassis team had turned the TR2 into a viable sports car (with Ken Richardson doing all the development driving)—could now turn his attention to the entire range.

Webster signing up Simo Lampinen for the rally team.

Webster signing up Simo Lampinen for the rally team.

This was not a universally popular appointment. One faction, supporting Lewis Dawtrey, one of Grinham’s long-serving deputies, has never forgiven Webster for displacing him. Webster the pragmatist, however, then used Dawtrey’s expertise as much as possible, especially in formulating plans for a new overhead-camshaft engine family in the mid-1960s. Webster was the archetypal ‘4B pencil’ designer who would sweep through a design office, drawing on his colleagues’ schemes, driving all the prototypes when they were ready, always keen to get his products involved in motorsport, particularly the Le Mans 24 Hour race—and always ready to try something new.

Ray Bates (later to become technical director at Longbridge) told me, “Harry was the great ring-master. He would inspire us, suggest what he wanted, then leave us to get on with it.” In the late 1950s, a new TR sports car had to be finalized (stylist Michelotti was Webster’s choice), a replacement for the Standard Vanguard was developed, a six-cylinder engine appeared and, at Alick Dick’s insistence, a new tractor was developed to compete with the Ferguson project which Standard had just dumped. P.R. man Robin Penrice once recalled that, “There was no Product Planning at Canley at this time. It was just a case of Alick Dick, Webster, George Turnbull and Martin Tustin getting together to decide on new models.”

Weekends and Racing

In the 1960s, it was never easy to find Webster in his own office. If he wasn’t in the drawing offices he was in the experimental workshops, maybe on the road in a prototype, or away in Italy to see Giovanni Michelotti, the stylist. Many years ago, Harry’s wife Peggy told me that in 1957 they had been on holiday in Italy, and that Harry called in on Michelotti to discuss the lack of progress with the new ‘Zobo’ (which became the Herald in 1959) project: “He said he wouldn’t be long, so my daughter and I settled down to wait. When he came down at midnight, nine hours later, we were still in the car, fast asleep.”

“He never gave us much notice,” workshop manager Tony Lee recalled, “and he told us exactly what he thought of each car when he brought it back.” In the 1960s such journeys became routine, were often completed solo, and made Webster the most hands-on, committed, technical chief of his era.

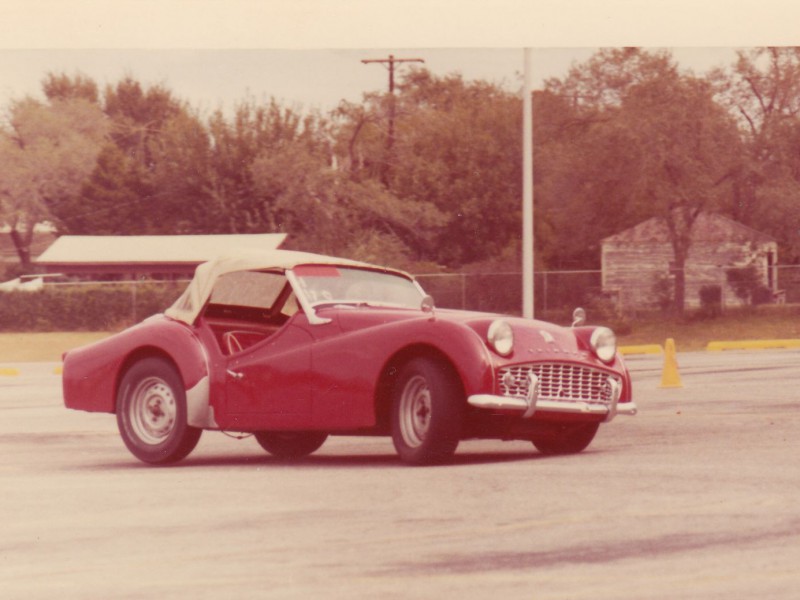

Deep down, too, he was a sporting driver, which might explain why he and motorsport boss Ken Richardson came to dislike each other so much. After the financial collapse of 1961, motorsport was cancelled (Leyland said they could not afford it), but Webster eventually wanted to get back into the swim, on his own terms, which explains why Richardson had to go. “Harry wanted to get back to Le Mans,” a colleague recalled, “but control the program. Harry squeezed money out of Stanley Markland, decided that we should use Spitfires, and his staff did the rest.”

Webster with the Duke of Edinburgh, showing him ADO 67, which became the Austin Allegro, at a secret viewing at Longbridge.

Webster with the Duke of Edinburgh, showing him ADO 67, which became the Austin Allegro, at a secret viewing at Longbridge.

“He was a quick driver,” test driver Gordon Birtwistle commented. “The best way to demonstrate the handling was to put him in the car with us—then he would insist on trying it for himself.” Roy Fidler, on his way to becoming British Rally Champion in the mid-1960s, remembers suffering an engine failure, and being called in to Webster’s office: “Harry waved a broken con rod at me, and I feared the sack. Then he said: ‘I want to thank you, Roy, for doing this! We’ve already identified the problem, and made changes to the machining. You’ve saved us a lot of trouble.’ He was a great guy.”

By comparison with BMW, Ford or the Rootes Group, Webster’s development budgets were small, but he inspired a small staff to get things done impossibly quickly. Michelotti reacted to his dreams of building a ‘Herald sports car’ (the Spitfire) by building a single prototype in 1960. Webster approved Michelotti’s style, but Standard’s financial collapse meant that the car had to be stored under a dust-sheet. It was his persuasive powers which saw Leyland approve it as the first of many new projects. “We took ‘Bomb’ from prototype to production car in 15 months.” his deputy John Lloyd remembers. “An impossible schedule, but great fun. Then, a month after launch, he and I took two Spitfires to the Turin show—and got stuck in snow on the Mont Cenis pass.”

Innovation and Swiftness

By keeping it simple, and using ‘building block’ engineering wherever possible, those were the days when three or four prototypes were enough to develop an entirely new range, and when ambitious personalities could get things done. First at Banner Lane, then at Canley, a small team designed everything except body structures. Along with transmission guru George Jones, it was Webster himself who sketched up the very simple front-wheel-drive (1300) package which was cheaper, just as effective and more reliable than anything wrought by Alec Issigonis.

Webster the enthusiast made sure that Triumph sports cars got disc brakes, wind-up windows and independent rear suspension years before MG followed suit. He also listened hard to what his US concessionaires requested—and gave it to them. Triumph, too, was the first in the UK to take a brave pill and use Lucas fuel injection.

For Webster’s Triumph team nothing, it seemed, was impossible. When everyone else suggested that the Spitfire engine could never produce 100 reliable horsepower for the Le Mans 24 hour race, Webster told Ray Bates—not Cosworth, not Downton, not Lotus, but his own team—to make it so. Using an already-existing prototype eight port head and a mountain of test bed time, this was done. Not only did the Spitfires complete the 24 hours—twice—and succeed in the Tour de France, but they defeated ‘works’ Sprites, Midgets and Alpine-Renaults on the way.

Webster (right) and Martin Tustin with the original Triumph Herald Coupe.

Webster (right) and Martin Tustin with the original Triumph Herald Coupe.

By the late 1960s, Webster was still in full flow, and Donald Stokes gave him his head. After a visit to Turin to see Michelotti, he came back with a drop-top prototype which became the Stag. Having adopted Lewis Dawtrey’s scheme for slant-4/V8 engines, he pushed them through Leyland’s approval system, well before Donald Stokes inspired the birth of British Leyland, and moved him to Longbridge. Webster’s replacement at Triumph was Spen King, who soon realised just what miracles had previously been achieved at Canley. Even so, Webster’s ‘fairy dust’ left the building with him, and he never got a chance to repeat the treatment at Longbridge.

In twenty years, Standard’s one-time ‘Apprentice of the Year’ helped transform a dull company to one whose products were positively trendy and successful. Because his colleagues all seemed to have so much fun, they produced new models much quicker than their rivals, and made money for their bosses, too. “We all used to enjoy getting up on Monday mornings and going to work,” Ray Bates told me, “there was always so much going on, and we seemed to achieve a lot. Harry made all that possible. Without him, we couldn’t move as quickly.”

First-ever TR2s reunited. Webster pictured with then-owner of TS1, Joe Richards of the USA.

First-ever TR2s reunited. Webster pictured with then-owner of TS1, Joe Richards of the USA.

Many years on, and long retired, Harry Webster became the icon of every Triumph one-make club, yet was still astonished by this fame. “We were only ever doing a job,” he tells me. “We never wanted fame like this. It is an honour to be recognised, but we were definitely not reaching for that at the time.”

Yet in 2004, when the time came to re-unite the world’s two original TR2s, there was only one place their owners wanted them to be—on the lawn of Harry Webster’s house near Coventry, with the Great Man able to inspect them. He enjoyed that—and so did we.

'Harry Webster – My Technical Mentor' has no comments

Be the first to comment this post!