by John F. Quilter

I saw my first British car when I was just a small boy living in Charleston, South Carolina. It was an Empire green 1953 Morris Minor that lived across the street from my house. Something clicked and the British car became a lifelong interest, or maybe even an obsession. Fast forward to leaving the US Navy as an officer serving on a replenishment ship in the Gulf of Tonkin—I was looking for a new, hopefully lifetime, career. I was driven to find something related to the British car world. I wanted to go into the industry but remain in the San Francisco Bay area. As luck would have it, there was a zone office of British Leyland Motors, known as Leyland Motor Sales based in the small suburb of Brisbane, California, not all that far from where I was then living. So I began to stop in and ask about a job there, any job. Once I could get beyond the attractive but snippy young receptionist and have a conversation with the operation’s accountant who obligingly came out from the back room to greet me, I could express to him my fervent desire to work there. I always referred to the latest Wall Street Journal article about the rocky times that British Leyland was going through but wished them the best. Bear in mind this was 1975, about the time that the British government was about to rescue BL from financial ruin with the loss of hundreds of thousands of workers in the UK.

I made this sojourn to the Leyland Motor Sales offices about every six weeks to reinforce my job seeking wishes with the office accountant, Gregory Datig, who got to know me after a while and was never reluctant to chat with me for a few minutes. He was a former Triumph fellow having started with a Triumph distributor in 1957.

Finally, after a number of months of visits, my persistence paid off and I got a phone call that the Zone Manager and Zone Service Manager wanted me to come in for an interview. I jumped at this invitation and arrived at the appointed time for the interview, which was, as I recall, perfunctory. I did not even have a resume but talked a good story, demonstrated my knowledge of the BL products and the corporate structure and situation all the way back to the UK, based on my WSJ knowledge. Maybe arriving in an Austin America solidified my company dedication.

It seemed from the interview that there was a huge backlog of warranty claims from the dealers in Northern California and the Pacific Northwest. I was to be hired to process warranty claims and reduce the backlog, which the retailers were complaining about as they were not getting reimbursed for their warranty work. Since I did know all the BL product line which comprised the Jaguar XJ6 and XJ12, E type V12, the Triumph Stag, TR6, Spitfire, GT6, MG Midget, MGB, Land Rover 88, Austin Marina and I knew the difference between a Borg Warner Model 12 gearbox and an SU carburetor or a Smiths speedometer, I was qualified for the position of warranty claims assessor. Soon it got down to what salary would I require. Being intent on getting in the door and not wanting to over price myself, I said, $165 a week would be acceptable. The Zone Manager’s immediate response was: “Oh no, we could not pay you that, it would have to be $195 a week” which resulted in no objection from me.

So, I was in. A dream come true. I really do not know how they got me on the payroll as the company all the way back to the UK was in dire straits and about to be taken over by the UK government, or go bankrupt. Surely there must have been a hiring freeze?

On the morning of April 7, 1975, I walked in wearing my professional looking coat and tie and was shown to a back room in the building where there was one older gentleman—a very long-time employee who was processing claims, slowly. But all around the perimeter of the room were Wrigley spearmint gum cardboard boxes filled with unprocessed claim forms received by date. There must have been thousands of them! Understand, this era was the absolute nadir of British Leyland product quality. If anything could go wrong, it did. From faulty assembly, to bad quality components from the likes of Lucas, Smiths, Clearhooter, BorgWarner, Girling, Stromberg—you name it, it was likely to be a failure waiting to happen. Customers were irate; dealers struggled to repair cars, often only to have the same replacement component fail yet again! And to top it off, the distributor was more than slow in paying the claims. In this era, these cars only had a 12-month, 12,000-mile factory warranty, but that was enough to generate massive numbers of claims. And BL UK was blindsided by the recent Federal adoption of a 5-year, 50,000-mile emissions warranty on everything from catalytic converters to Lucas electronic ignition systems, which furthered the tidal wave of claims. Remember those potted Lucas electronic ignition modules that bolted to the side of the distributors? And they were fit to every car post 1975!

Every typed claim had just one fault per form, which was in triplicate, had to be “coded” with a fault code corresponding to the failure, the model code entered, the labor claim verified, the sale date of the car verified, and any sublet work documented with an attached bill. I was provided with a set of factory labor time guides for all the models of the cars that could conceivably still have warranty coverage, a fault code book, a desk, chair and boxes of claims. The older gentleman in the back room gave me some rudimentary training and set me free to whittle away at the mound of backlogged claim forms. He knew his work well but was more than slow. He was also tasked with checking in all the proprietary parts (Smiths instruments, Lucas items), which had to be received from the dealers and ultimately sent to Smiths or Lucas for their confirmation of the failure which, if verified, resulted in some financial reimbursement to BL. But they had an amazing ability to declare it “no fault found.”

The process was: once the claim document was coded, it went to a key punch operator who punched in the information whereupon the mainframe computer in our headquarters in Leonia, New Jersey, generated a dollar value and posted this to the dealer’s account. Once the New Jersey headquarters became aware that the Northwest Zone had a new claims assessor they sent the National Warranty Manager, Bill Greehey out to fine-tune my somewhat lacking training in this coding process.

I was working on building a good reputation and worked as expeditiously as possible. I often took a bulging briefcase of claims home to process on the dining room table, but it was a never-ending treadmill. The same defects repeated themselves year after year as there was seemingly no effort to address the chronic issues. The sports cars kept selling as there was always a new crop of young buyers, ignorant of the quality issues but still wanting a fun car, and we had quite a variety and price range. As sales continued, so did the lag in warranty claims, and my job security.

One memorable issue that stuck with me was with the MGB. The armrest had a peg attached to the bottom and a latching clip in the plastic console base. The armrest hinge was a bit flexible, so it was easy to push (slam) it down off-center to the latching clip. This resulted in the clip breaking the plastic console and the clip falling into the area below. The warranty repair was to change the entire console which entailed removal of the radio, all rather time consuming at ever-rising dealer labor rates. These failures went on for years, and I saw way too many claims on them. We had a document called a Product Quality Report (PQR) in which our company service staff, or the dealers, could report to us an issue and even propose a solution. Being an employee who desperately wanted to see fewer warranty repairs and more satisfied customers (and company survival), I took it upon myself to complete a PQR on this. My solution for the factory was to eliminate the latch entirely and replace it with a square of Velcro that would serve to hold the armrest down without rattling or moving. I wrote this up, annotated the amazing frequency of claims on this, and submitted it to my then boss the Zone Service Manager, a very old-school Englishman who was likely more than twice my age and never could really relate to an earnest “young buck” like myself. I presented this PQR to him in the middle of the central office. To my horror and disappointment, he read it over, and simply tossed it into the nearest wastebasket, apparently believing it was likely nothing would ever be done and it was hopeless. From that point forward I knew the future of the sports car was doomed.

In the US the sports cars did go away around 1980, and we downsized to just the more profitable Jaguars, going from some 50,000 units sold a year to about 3000. That entailed substantial layoffs, but since warranty claims always lagged sales, I survived in my position, which gradually morphed into a more outwardly facing role with the retailers in warranty administration and training. Along about 1980, with the shrinking of the US business, British Leyland USA bought all the independent regional distribution operations. That resulted in my office more than doubling its territory to include Southern California, Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, and as far east as El Paso. In the later part of my career I think I visited every Jaguar and Land Rover dealer from Chicago to New Orleans to San Diego to Honolulu to Anchorage for training and business consulting work. And some of those visits are a tale of their own.

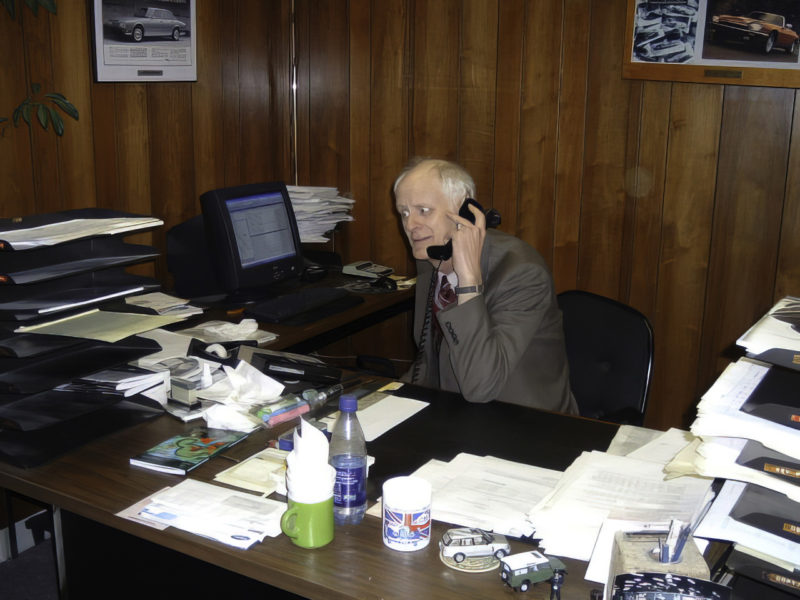

So to make a long story short, as Western Region Warranty Manager of Jaguar Land Rover North America, I survived 32 years in the industry, retiring in February 2007 as our then owner, Ford Motor Company, was on the ropes and downsizing for survival. I came in to a company on the ropes and left with a company on the ropes! MM

'John F. Quilter, Warranty Claims Assessor' have 4 comments

May 23, 2021 @ 11:14 pm Tatiana

It is a beautiful story, extremely well written. It is not really about cars, it is about whole generation , about their devotion, passion, love and life. I really enjoyed it. Thank you!!!

June 27, 2021 @ 10:38 am Glenn Lenhard

I worked at a Leyland dealer in 1975. Nearly all of the horrid Lucas Opus distributers were failing on the road, but of course by the time the car came in on the tow truck, it had cooled down and the car started. We replaced them by the hundreds. And then the very same ones would come back from the Warranty processing department as “tested good”.

Perhaps John was puzzled when he started receiving undeniably bad distributers from us. Our shop Forman (British born and trained) told us just to plug them in the wall and fry them for a minute or two before sending them in. It gives a totally new meaning to the term “let the smoke out”!

I even have in my archives a TSB (technical service bulletin) from Leyland admonishing the dealerships for sending so many perfectly good Opus distributers in for warranty, and to learn how to do our job better!

April 25, 2023 @ 8:55 pm John Quilter featured in Moss Motoring, May, 2021 – British Motor Club of Oregon

[…] https://mossmotoring.com/john-f-quilter-warranty-claims-assessor/ […]

October 13, 2023 @ 3:40 pm Sandy Ericson

Hello John,

We also live in Eugene and love the Morris Minor. We have one we would like to sell as we are now downsizing.

Can you offer some ways to do that or would you be interested yourself?

Many thanks!

Sandy Ericson