by Graham Robson

(written shortly before his passing in 2021)

When talking to North American Triumph enthusiasts, the first thing I try to do is to remind them that the famous TRs were not the only sportscars the company had. If you total up the global sales figures, in fact, there were other models which did even better. That is usually the first controversial point I make—the next being to point out that it was the Triumph Herald (a car which had no appeal to North Americans) that made most of the profits which kept the company alive in the 1960s.

So, this story really covers 1959 to 1971, twelve years in which Triumph, rescued from imminent bankruptcy by Leyland Motors in 1961, sold more than 920,000 of what all British enthusiasts call the ‘Herald family’—more than 310,000 of which were the ever-popular Spitfire sportscar. And yet it all came about by chance—in a deal originally discussed between Triumph’s technical chief, Harry Webster, CEO Alick Dick, and a rather shadowy entrepreneur called Raymond Flower, on an entirely different subject.

Way back in 1957, Raymond Flower (an independent British business man with a colourful reputation), was based in Egypt and started work on a scheme to make and sell economy cars there (that project failed, by the way, and it plays no further part in this story).

In this process he approached Standard-Triumph about providing engine and transmission supplies, and as an aside he tossed off the casual remark that he could easily commission a suitable body style, and get it done very quickly, from a contact he had in Italy. He then quoted the price he would have to pay, which quite astonished the Triumph bosses. Stunned, they got him to reveal his source—which was that of Italian stylist Giovanni Michelotti. Standard-Triumph quickly approached Michelotti for ideas, liked the speed and flair that he showed, and rapidly hired him to work his genius for them. And the rest, as they say, is history.

It was Michelotti, therefore, who created the original style for the Triumph Herald. But it was force of circumstance which led to that car being based on a separate chassis frame, and which allowed all sort of other styles to be built on top of it. The company had wanted its habitual body builders, Fisher and Ludlow, to produce new monocoques, but as that company had recently been bought by their dreaded rivals, BMC, they were rebuffed, so the separate frame/body Michelotti proposal was a heaven-sent opportunity to solve a big problem.

At first glance, having to develop its new car around a separate ‘old-tech’ chassis frame looked like a step backwards, but the engineering team soon came to treat it as a bonus. For one thing, it was quick and straightforward to do (senior Triumph engineer David Eley once told me: “Any draughtsman could design a frame”), and it was a much cheaper solution than to commission a specialist like the Pressed Steel company to develop a monocoque! For another, Standard-Triumph found to their delight that they could tackle a restyle, a shortening of the frame, or even a major re-jig, such as enabling the Spitfire to run with a true ‘back-bone’ derivative, without taking years, and investing millions, to do the job.

Not only that, but Harry Webster later pointed out that the company still did a lot of CKD (Completely Knocked Down) business with its overseas subsidiaries in those days, and that the frame could act as its own jig without any extra hardware being needed. There were other bonuses, which the company would publicize to its advantage in the next decade—all-independent suspension and the use of rack-and-pinion steering were obvious advances, but the incredibly tight turning circle (just 25 feet, curb-to-curb) was surely the clincher.

The original 948cc-engined Heralds might have been small but neatly-styled, yet they struggled to reach 80mph flat out. Neither the four-seater sedans nor the fastback coupes, which went on sale in 1959, were of any interest to North American buyers, for they only had 35bhp. I believe that it was tuning-guru ‘Kas’ Kastner who once commented that: “If you couldn’t beat 70mph by the time you reached the bottom of the entry ramp on Californian freeways, you were dead,” which was a valid point.

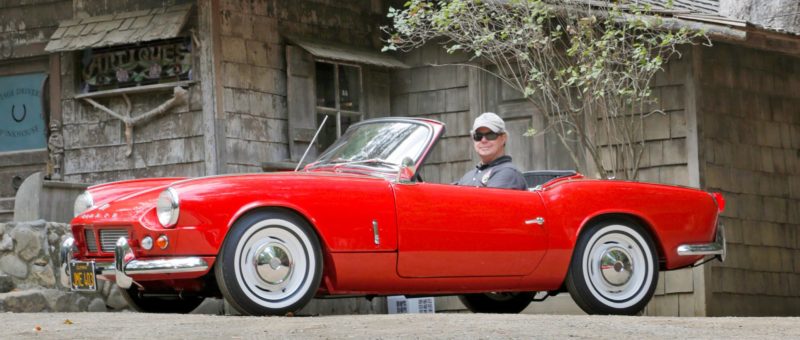

After Leyland bought up the company, ushered the 1147cc/39bhp engine into production, renamed the car Herald 1200, and boosted the build quality, things began to improve. Not only that, but by this time Harry Webster and Michelotti had also got together to produce a short-wheelbase/modified-chassis pretty little two-seater sports car which they coded ‘Bomb,’ hoped that Leyland would like it, and soon found it approved for sale. By the end of 1962, ‘Bomb’ had become Spitfire, the engine had been persuaded to produce 63bhp, and with looks aided by a top speed of 90mph it was an instant success.

American customers, who had just been treated to the offering of the new TR4 sports car (which had also been styled by Michelotti), were delighted to have a choice, for in 1963 the TR4 cost them $2,849, whereas the appealing little Spitfire could be theirs for only $2,199. Incidentally, the Laycock overdrive (a smaller relative of that already available in the TR4) was soon made optional. The Spitfire immediately began to sell faster than the combined sales of the rival Austin-Healey Sprite and the MG Midget—and it would continue to do so for the next seventeen years.

By then, too, the Spitfire and the TR4 had been joined by yet another Herald-derived car, called the Vitesse in Europe, and the Sports Six in North America. Think of a car which looked rather like the Herald, though it had a fashionable four-headlamp nose, and which ran on a beefed-up version of the same chassis, wheelbase, tread and suspensions—but it hid a 70bhp/1596cc six-cylinder engine under the bonnet. That sounded good, but as it cost the same sort of money as the TR4, and had to compete with many ‘domestic’ rivals, it was not a success. Technically, the four-cylinder Spitfire engine, and the six-cylinder power unit had much in common, so there were all manner of financial and servicing gains to be made.

Even so Triumph’s importers could soon afford to ignore the Sports Six’s failures, for there was more, much more to come from the sporting models. In the USA, heroes like Bob Tullius, and Kastner could hone their TR4s to dominate SCCA racing, while the UK-based factory developed fastback Spitfire race cars that became class winners in the Le Mans 24 race and were competitive at Sebring, while the 1.1-litre ‘works’ rally cars were amazingly successful in European events. The fact that the cars had carefully re-shaped noses which looked like those of Jaguar’s famous E-Type, was a great boost to its enthusiasts, too.

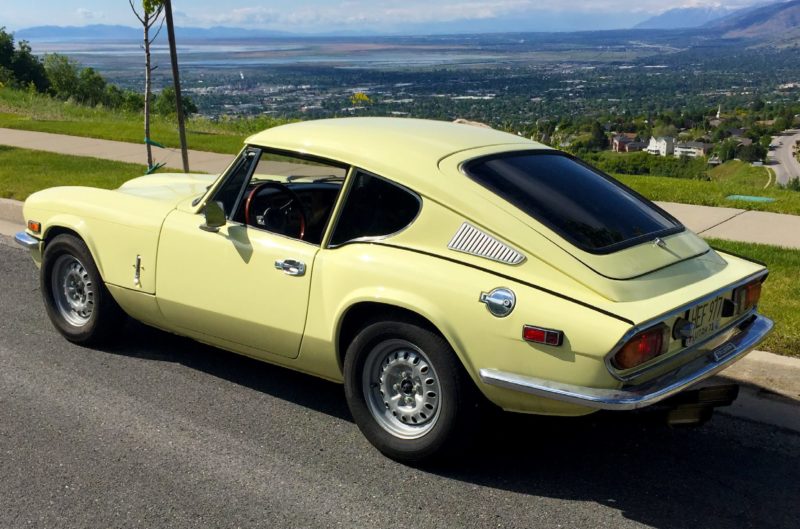

All of this would have encouraged some companies to sit back, sigh happily, and enjoy the success coming in, but Triumph had more ideas. Work up your own mental ‘configurator’ and combine the Spitfire’s chassis with a fastback body style as already seen on the ‘works’ competition cars, line up a larger and power-tuned version of the Sports Six’s six-cylinder engine and—as if by magic—you had a new 100mph sports coupe, which could be called GT6.

Not only did this power unit fit neatly under the hood of the existing Spitfire front end, but as a 1998cc engine it produced 95bhp, and gave the new car a top speed approaching 110mph. On sale in the USA from early 1967, it cost only $2,895, so it got off to a very good start.

Within a year, the company had replaced the dear old TR4A (the last to use the company’s famous ‘wet-liner’ engine) with the TR250, which might have looked the same, but just happened to share its six-cylinder engine (this time with 104bhp) with the GT6. At the same time the GT6 was improved in several ways and became ‘GT6 Plus,’ and for one year only rejoiced in having 104bhp, too.

In only five or six years, therefore, Leyland had transformed the fortunes of their North American sales operation, changing it from selling just one car—the aging TR3A, which was really dying on its feet in 1961—to one with no fewer than three fresh and modern models, the Spitfire, GT6 and TR250. Because Leyland had become British Leyland in 1968—which meant that Lord Stokes and his cohorts therefore controlled both Triumph and MG—there was no way that a marketing fist-fight should be allowed to break out between the two famous British brands, and it all looked promising.

Then, slowly at first, but more and more obviously in the years which followed, the ever-increasing USA legislation, which enforced new exhaust emissions, crash tests, and secondary laws, began to affect the sale of all British cars. To meet the cost of all these new rules, prices had to rise, performance went down, and the cars became less attractive to buyers. After the Heralds and Vitesses were dropped from the British market in 1971, Triumph dealers in the USA braced themselves for what would follow. Sure enough, the GT6 was dropped at the end of 1973, which left the gallant little Spitfire to battle on alone until 1980. The company accountants, however, must have been pleased, for the ‘Herald-chassis’ generation of Triumphs had lasted in Coventry for no less than 21 successful years.

Even so—and cheer up, all you Triumph lovers—the 1960s was a great time to enjoy sportscar motoring in North America. And thanks to enthusiasts, young and old, the cars of that era are still a joy today. MM

'One Design, Many Derivatives' has no comments

Be the first to comment this post!