I was devastated to learn of the closing of the Abingdon factory. The date was October 22, 1980, which, just my luck, happened to be my birthday. My friend Peter Franklin who was Public Relations Manager at the time, called to tell me the news. Management closed the doors two days early to avoid any unruly scenes from MG enthusiasts who had promised to demonstrate on Friday the 24th. For one of the few times in my life I went to the pub and had a couple of drinks too many to drown the sorrows.

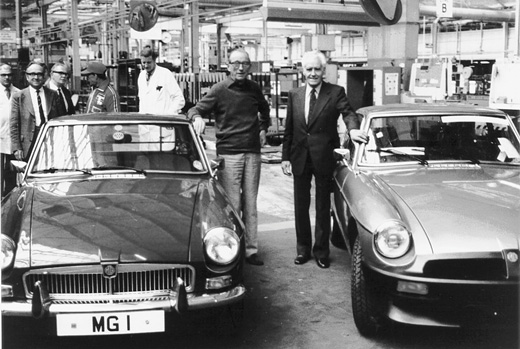

Looking back over a long personal history with the MGB, I don’t find myself at a loss for words, but I’m searching for words that haven’t been retold countless times. Many books, and thousands of articles and photographs have covered the details of the various models produced. But, I feel that if it were not for the foresight of those I warmly call the “B” Team who envisaged the MGB, some of whom I knew personally, none of the 50 years of memories we are celebrating would have happened. Over a span of eighteen years, from 1962 to 1980, a total of 512,243 MGBs were built by hand and pushed up the line manually. I am honored to say a few words about the people responsible.

Looking back over a long personal history with the MGB, I don’t find myself at a loss for words, but I’m searching for words that haven’t been retold countless times. Many books, and thousands of articles and photographs have covered the details of the various models produced. But, I feel that if it were not for the foresight of those I warmly call the “B” Team who envisaged the MGB, some of whom I knew personally, none of the 50 years of memories we are celebrating would have happened. Over a span of eighteen years, from 1962 to 1980, a total of 512,243 MGBs were built by hand and pushed up the line manually. I am honored to say a few words about the people responsible.

From Fields to Wheels

Prior to MG’s existence, the primary industry of the surrounding area was agriculture. Most of the workers originally employed at the “Gee” were ex-farm laborers. When William Morris acquired the Pavlova Leatherworks facility this was the first time they had ever had an indoor job.

Those employed by MG were one big family, and you couldn’t get a job at the factory unless you knew someone who worked there. They were a happy, devoted bunch who worked six days a week and took their Sundays religiously either by attending church or tending to pints at the local pub, or enjoying one after the other. Very few could afford cars, and so when quitting time came around, roads were nearly gridlocked with bikes.

Despite, or perhaps because of their modest lifestyle, Abingdon employees were proud. It also engendered some jealousy between Longbridge and Abingdon where with a bitter spit it was said: “They build one car, per week, per man from John Thornley on down to the office boy and all they got in the way of mechanical equipment is a wheelbarrow!”

John W. Thornley

The composition of the “B” team covered all aspects of management being led by John W. Thornley, a man known to MG enthusiasts across the world as “Mr. MG.” Born in London in 1909 and starting life as an accountant, he asked for and got a job with MG after writing to Cecil Kimber and suggesting that a club be formed for MG owners who had purchased the little M-Type two-seaters of the day.

1934 saw Thornley appointed to the role of Service Manager and he became closely involved with the competition side of the MG Car Company, including running the “Cream Cracker” and “Three Musketeers” trials teams. He served in World War II reaching the rank of Lieutenant Colonel before returning to Abingdon in 1945. Thornley was a real leader, and together with Syd Enever was instrumental in forging the whole history of post-war MG especially the MGA and the MGB. He controlled the Abingdon factory as General Manager from 1952 to 1969 and in total spent almost 40 years of his life there.

An example of Thornley’s involvement and passion right up to the end was told to me by Facilities Engineer John Seager: “One day my phone rang and I answered rather sharply having had several testy phone calls that morning. After a pause I heard a voice say, ‘I’ve had a morning like that too, John.’ It was JWT himself.” According to Seager, Thornley was forthright in calling a spade a shovel. He fought for MG’s interests spiritedly as evidenced by the words he spoke out against the direction Leyland was taking: “…despite the fact that there are people in the USA who still derive their bread and butter from the sales of MG’s. But Leyland was so convinced that the sun shone out of Triumph’s exhaust pipe that they then go and produce this bloody stupid TR7! In another year it’s going to be as out of date as last year’s dress! Fashion—gimmicky fashion—no chance of lasting long enough for any sort of return on invested capital. If someone would like to get their finger out NOW! We could get down to it in time for when MGB sales begin to fall off. What are the chances of that? God only knows—I don’t.”

Syd Enever

Thornley worked closely with a modest but brilliant engineer named Sydney Enever. Born in 1906, Enever started as a messenger boy for Morris Garages before even Kimber arrived in 1920. However, Kimber recognized Enever’s potential and in 1929 he named him Chief Experimental Engineer. Henceforth Enever was involved in each and every modern MG, until his retirement in 1971.

Enever’s task of following up the successful MGA was monumental. The MGB was the first monocoque bodied MG sports car ever to emerge from the factory. All previous MG’s since the 1920s had employed some kind of a chassis, but in a radical departure from tradition the “B” Team decided that unitary construction was the way to go. In this small factory, two very distinct production lines operated until the last remaining MGA body was placed on a waiting chassis.

Never without a cigarette dangling from his mouth, Enever did not always endear himself to his staff, as he had a habit of making notes on the back of cigarette packets, or even on the drawings produced by his staff, and then throwing them in the trash before communicating his ideas to his assistants.

Enever once said, “The MGB shape, though you might not realize it was basically borrowed from EX181. When we started the MGB we took this shell and developed it into a passenger car.” One look at the mid-engine, high-speed record breaking car and it’s evident that only a visionary engineer could conceive how the design of the EX181 could possibly evolve into an MGB.

Roy Brocklehurst

Straight out of high school Roy Brocklehurst joined Enever as a design apprentice in 1957. After serving in the R.A.F. he returned to Abingdon where he became Chief Chassis Draftsman, and it was in that capacity that he worked on the MGB designing a great deal of the mechanical layout of the new car. He had also worked on the MGA, the MGC and all the prototypes that never made it. Upon Enever’s retirement in 1971 he became Chief Engineer, but as the Abingdon MG era came to a close he went across to Longbridge to develop the MG Maestro.

Don Hayter

Thanks to the MGB I have more friends than I can count. I am fortunate that Don Hayter is one of them. Throughout the volumes of stories surrounding the MGB, Don’s dashing presence could often be seen and felt. Born in 1927, Hayter started out at Pressed Steel, the company that would later be responsible for building the MGB body shells. In 1954 he moved to Aston Martin, but in 1956 he found himself as Chief Body Draftsman, soon to be working alongside Brocklehurst. Once the MGB got the green light he was able to undertake the dash design, the windscreen and the hood. He also redesigned the rear suspension from that which had been proposed earlier.

Hayter took over the Development Department in 1968, and when Brocklehurst left in 1973 Don took over as Chief Engineer. He did a great deal of work on updates to meet safety legislation requirements for the US market. Don was one of the last people to leave the factory when it closed, and today in retirement still drives his MGB on the streets of Abingdon.

Other key players

Other key players

The development of the MGB was largely assisted by Terry Mitchell (chassis), Dicky Wright and Jim O’Neill (bodies), in addition to Des Jones, Don Butler and Denis Williams (all ex-Cowley employees). Peter Neal, an early MG apprentice, showed an aptitude for electrics. And the stalwarts of the Development Shop Alex Hounslow and Henry Stone—one of the original Insomnia Crew—were indispensable.

Whenever my wife Barby and I spent a day in Abingdon we always called in on Henry Stone and his charming wife Winnie. Once, attending an Octagon Car Club event we were loaned an expensive replica K3, fashioned by Peter Gregory which Henry encouraged me to drive, with himself riding shotgun enjoying every second as if he were fifty years younger. As Henry had been instrumental in developing the MG K3 during the thirties, I counted this a great honor. So we set off driving all over the Berkshire countryside with the snarling exhaust note of this magnificent machine echoing behind us. Suddenly Henry turned to me and shouted, “Do you fancy a cup of tea? Let’s go round to my house and Winnie will set us up with afternoon tea.” Soon we were ensconced in Henry’s garden enjoying the sunshine, living the good Abingdon life.

Meanwhile, back at the MG meeting, panic ensued, as people kept asking: “Where was Ken and Henry? They left hours ago! Had they had an accident? Had they piled up the priceless K3 replica?” They even turned with looks of concern to my wife Barby. All she could do was shrug her shoulders. When we did finally return, the look on the faces of the group showed how distressed they were for our welfare and safety, not so much for me, but for the esteemed man who played a major part in MG’s racing and record breaking.

About ten years ago I had the pleasure of compiling a little book detailing the skills and procedures that went into the manufacture of the MGB. This was eventually published under the title Aspects of Abingdon and is available from Moss Motors.

By Ken Smith

'The B-Team' has 1 comment

August 10, 2012 @ 3:01 pm Andy Graybeal

Lovely memoir. Being a TR4 owner, I might take exception to the author’s bias against Triumphs, but recognize that it was the “suits” that called the shots. If the TR7 was an unworthy alternate to a “new” MG, and was known for production problems, it could be blamed on inadequate development and the American EPA’s fickle requirements. Style-wise, if one were to make the black rubber bumpers body color, the car would be in keeping with todays cars, like ’em or not..

William Morris thought he was really doing the locals a favor by giving them work under roof. The Abingdon workers wouldn’t have been riding so many bicycles if Morris had learned from Henry Ford and paid his workers enough to enter the MG market and to adopt “modern” assembly line approaches. I guess progress is incremental and local.