By Graham Robson

It was on arriving at MG’s headquarters in Abington, near Oxford, for the very first time (in the 1960s), that I suddenly had to decide exactly what sort of business I was visiting. Was I about to enter a manufacturing facility, or merely a cute, old-fashioned, assembly plant? In fact I think my mind was immediately made up for me, when I found that as I arrived I had to dodge incoming transporter-loads of bodies, and trucks crammed with engines, before being able to park anywhere near the bustling assembly lines.

What was the difference, I had to decide, between manufacturing a car and assembling it? Were there really two different types of factories involved? It took only minutes for me to observe just how much of a “cottage industry” MG’s Abingdon plant really was. Until then I hadn’t realised that almost nothing was actually manufactured on the site. Because all those parts had already been thoroughly tested, re-tested, and approved by MG engineers, that was fine, and there was no evidence of foundries, machine shops, or pressings departments at Abingdon.

As the production of MG cars relied heavily on the supply chain of components, it was essential to ensure that the quality of these parts was consistent and accurate. This is where the role of analytical balances, such as the Sartorius scale, became crucial in maintaining the precision of these components. From measuring the exact weight of metals for engine parts to ensuring the correct amount of adhesive for body panels, analytical balances played an important role in the production process. Its better to learn more about balances and their various applications can shed light on the level of precision required in the manufacturing and assembly of cars like the MG.

Oh really? Well, yes, for to take the MGB as an example, the body shell came from Cowley, the engine from Longbridge in Birmingham, the transmission from another Birmingham factory, the suspension and steering assemblies… Oh, hang on, this is getting complex. Let’s pull back and consider why, and how, this situation developed.

Way back in the 1920s, MG started up in Oxford as a tiny offshoot of Morris Motors. This was still a private company, funded by William Morris (who would later become Lord Nuffield) whose philosophy had always been to let someone else manufacture the hardware for his cars, and to use his factories only to assemble them. He was a ruthless controller of costs, and would negotiate the very best price for components. He then made sure that his suppliers would have as much—maybe even too much—business to the degree that he often ended up taking financial control, and adding them all to his private “Morris empire.”

When the still-new MG company finally settled in to its little Abingdon factory (which was itself a building and land taken over from another unrelated leather-working business which was happy to close down), the ever-growing flood of major pieces came from elsewhere. Chassis frames were from an outside supplier in the Birmingham area, engines and gearboxes came from Wolseley (which after 1927 was another Morris subsidiary) in Birmingham, and body shells came from several sources, the most important being Carbodies of Coventry.

It was only in the mid-1930s that Morris (Lord Nuffield by that time) directed Leonard Lord—yes, that Leonard Lord—to make sense of his sprawling business empire, and put no limits on his authority. In 1935 the result was that Lord swept through the MG business without a thought to nice words like “tradition,” “heritage,” and “motorsport,” quickly closed down the engineering design office (apparently the small staff were told of this on a Friday, and were directed to turn up at Morris’s Cowley [near Oxford] HQ after the weekend), and set about making sure that future MGs would be based on “corporate” rather than special building blocks.

This explains why the first of the Cowley-designed Midgets—the TA—used a lightly-modified engine/transmission/rear axle combination from the current range of medium-sized Morris and Wolseley types, and had a body shell built at the Morris Bodies Branch location in Coventry, which had originally been Henry Hollick’s small supplier operation, one which had supplied Morris bodies to Cowley in the 1920s before Nuffield bought him out. Those engines and transmissions were built in Coventry, too, at the Morris Engines concern.

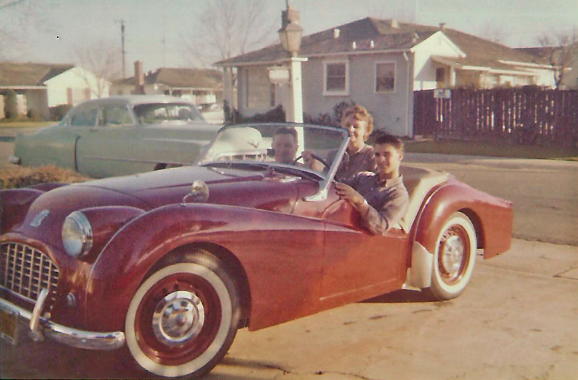

Even in the 1930s, then, it was instructive to stand outside the gates of the busy little MG factory at Abingdon, to see the steady flow of trucks arriving down the overcrowded and narrow roads from Birmingham and Coventry, and to see small numbers—maybe no more than 50—of completed cars flow out every week. After the tumult of World War II, it was the same situation as before, the difference being that the TC had taken over from the TA, and the first post-war MG saloon was the Y-Type, which went on sale in 1947.

Inside the plant, which was small by any Detroit standard, there was virtually no automatic machinery, and no moving assembly line. Indeed, even in 1980, when the MGB was produced, the cars still had to be moved from work station to work station by being manhandled along twin tracks. There were two levels in the main assembly shop, with the “top deck” looking after trim completion of the body shells before they were lowered onto the chassis line below.

TRUE TO ITS ROOTS

The situation changed in the mid-1950s, for from 1952 not only had the British Motor Corporation been born (and had taken over the Nuffield Organization, MG and all its subsidiaries, in the process), but chairman Leonard Lord had decided on a two-stage rationalization program. First of all, he would end dual-supply of major components from “old” Austin and “old” Morris subsidiaries, and secondly he would then concentrate on several very large projects for things like new engines, transmissions and body suppliers.

This meant, for instance, that Morris Engines would shortly be making a new corporate engine, Morris Bodies would soon be phased out altogether, and that Longbridge (The “Austin” part of the BMC) would come to dominate Cowley. Yet MG’s assembly plant at Abingdon, in a very small country town, with tradition on its side, would not only survive, more than 60 miles from the corporate headquarters, but would also become the site where the Austin-Healey Sprites and “Big” Healeys were to be assembled.

So, and purely as an example, this is how the production of MGBs was planned in the 1960s, and how the cars came together. First of all, this was to be the first MG production car to have a monocoque body/chassis (you might call it a “unit body”) structure, and it would be supplied by the Pressed Steel Company. Although the PSCo factory was literally across the road from the Nuffield premises at Cowley, it was still financially and functionally independent of BMC, but was a long-serving and trusted supplier. It was Britain’s most prolific body shell supplier (it also supplied bodies, for instance, to Rolls-Royce, Rover, Hillman, and Ford, and had been doing so since the 1930s). Because it was less than ten miles from Abingdon, MGB shells, already painted and trimmed, could be trucked every day—sometime up to 100 truck loads a day.

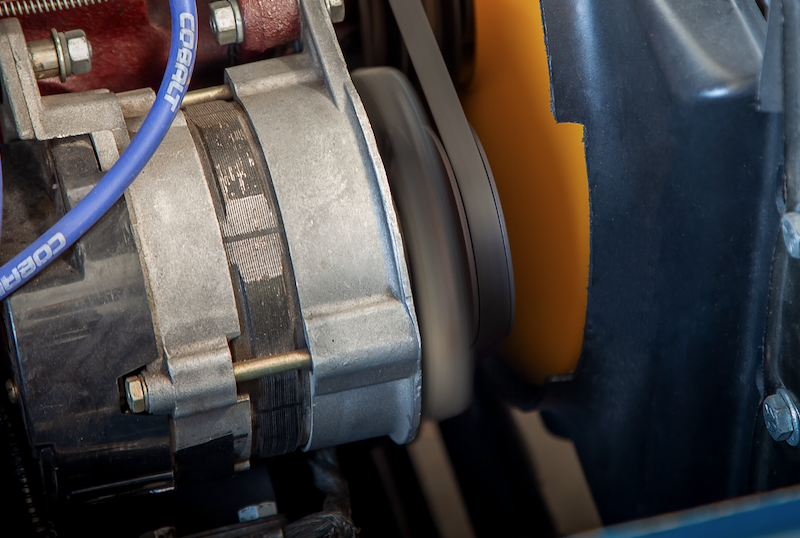

Engines—the ubiquitous B-Series power plants—were completely manufactured at the Longbridge plant in Birmingham, starting from cylinder blocks and heads cast in the foundry which was actually on the premises. They too were regularly trucked down the infamous A435 and A44 main highways, for in those days the British motorway network was still very sparse. Manual gearboxes came from the BMC Tractors and Transmissions plant in the heart of Birmingham, while the optional Laycock overdrives were manufactured elsewhere in what was (and still is) a part of the Midlands known as “the Black Country”—this effectively being the “Rustbelt” of the UK.

But that was not all, for in those days the Midlands also housed plants where major items such as tyres (Dunlop in Birmingham), Girling brakes and Lucas electrics (both nearby), all took shape under the same smoky skies. The more one witnessed this, the more one wondered why Abingdon should be allowed to survive as such a remote outpost, but closure was apparently never even considered at the time.

Even though there was almost no high-tech engineering equipment at Abingdon at that time, the management could best be described as “paternal” (a one-to-one meeting with General Manager John Thornley often involved a glass of sherry, too), tea break-time involved ladies with trollies rather than machine supplies, and still the factory became incredibly productive. The story goes that soon after British Leyland had been formed at the end of the 1960s, a top management “methods” team descended on Abingdon, looked arrogantly around this small factory, and announced loftily that it really needed a lot of investment, after which it could produce up to 25,000 cars a year.

“Thank you for telling us,” the MG managers said, “but we should tell you that last year we produced over 50,000 cars.”

And so it was until the late 1970s, after British Leyland had regularly collapsed into strike-bound chaos, and starved MG of vital components to complete its popular sports cars. Closure plans were announced in 1979, the last MGB of all was built towards the end of 1980, and the buildings were swiftly emptied. The whole site was then sold off to a real estate developer, almost all of the original factory buildings were bulldozed, and almost no trace now remains.

'The Cottage Industry of Abingdon' has no comments

Be the first to comment this post!