By Richard Santucci

Fred Dagavar was a man’s man. A swashbuckling Errol Flynn type complete with manicured moustache. He possessed a distinctive, deep, gravelly, Armenian accented voice and was arrested in 1935 for brandishing a gun at a man after a fender bender on, where else, Gun Hill Road. “I ought to give you a dose of lead poison and sign your death warrant!” he allegedly said to the president of the Bathgate Taxpayers Association after his car was run into. He received a $600 fine.

Fred was also a World War II veteran and had an artillery shell holding open the door of his business establishment on the Grand Concourse in the Bronx, but I knew him mostly as a racer.

As far as I could tell, Fred’s racing history went back to 1939, when a race that he had applied to be in was cancelled because Hitler had annexed the Sudetenland. Legendary racer, Ralph DePalma, personally wrote him the cancellation letter and sent him back his $25 entry fee. I have the letter.

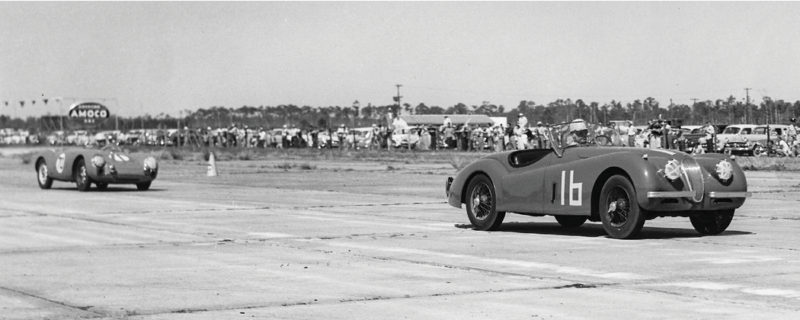

Fred raced throughout the 1940s and ’50s and competed at Sebring at least five times, always in Jaguars. He was also a friend of Bill France. As such, he was a co-founder of NASCAR with France and served as its first competition chairman.

I remember as a small boy accompanying my dad to Dagavar & Dagavar—a DuMont radio and television network factory store that Fred owned. They would discuss Hi-Fi, drink a bottle of Scotch, and talk about his racing days. Mostly I remember the conversations about Fred’s Jaguar. To a seven year old, hearing the tales of his exploits in this car, I was transported to a mythical place, one of speed and daring. I recall my mother saying how he slid the car around corners when he took it “down the shore” to Long Branch, New Jersey.

In the early 1970s, I was delivering an order for my grandfather’s butcher shop, driving my Mk IX Jaguar on the Grand Concourse. A thought crossed my mind while passing Fred’s business establishment. I stopped and said hello, and then I took a breath and asked him if he wanted to sell his Jaguar. It was a car that I had never seen in person. I only knew stories of it, like how Fred drove from New York to Sebring, Florida, in 1955, raced, finishing 46th, and drove it back home.

In his deep, accented voice he said, “Vell, seeing as I’m pushing 70 years old, maybe it’s time to let it go.” I asked him how much, he threw out a price, and I said I would be right back with the money. I was in heaven. I had a Mk IX saloon and a race car!

Heaven was short lived when I went to the open-air parking area under the concourse and saw the magnificent vehicle of my dreams. It had three flat tires, was painted white with what must have been a whiskbroom, had parts in wooden milk crates and a disintegrated interior. I guess that was when I first realized that I was an optimist.

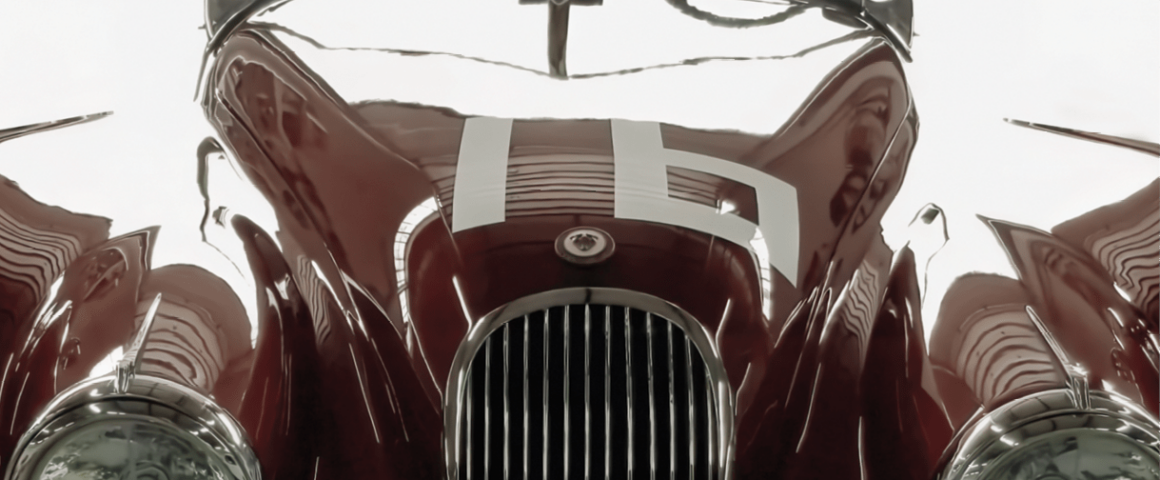

On the positive side, all the parts were there with matching numbers. And, the copious amounts of oil that it leaked had preserved the undercarriage as if it were covered in cosmoline. On top of that, Fred had given me paperwork that he thought might come in handy, including the original purchase order and bill of sale, and the technical inspection punch card for the 1955 running of Sebring. Then he made me scribble a few notes on the back of a piece of scrap paper. He said, “It’s important that you know these things: factory race prepared, close-ratio gear box, high-ratio steering, built all the way loose, 3:31 rear end, and it’s a 1955 car in a ’54 body.” He also said that it was five different colors of red when it arrived.

“Fred,” as the car came to be known, sat around for years as I finished college and chiropractic school. I accumulated parts. No internet then, so writing letters to Zurich became a normal way of life. When fax machines came into vogue, I thought I hit the lottery.

I finished restoring the car for the first time in 1979. When I brought it to Joe Maletsky at Motorcraft Ltd., in East Rutherford, New Jersey, for a mechanical rebuild, I told him that it was special, it had a “C” type head. He looked into the valley between the cylinders and said, “No way, there’s no big red ‘C’ in the casting.” I showed him the purchase order delineating the purchase of a “C” head for an additional $150, and he said it just wasn’t there— even though the numbers matched.

Lo and behold, I was working one day when I received a phone call from my “mechanic.” It didn’t matter how backed up with patients I was, when Joe was on the phone I answered. There are priorities. I will never forget his words. He had disassembled the engine for a rebuild and saw something that was out of the ordinary. He said, “You’ve got sneaky valves.” I asked him what he meant, and he said that I was correct, it was a C-Type head but one he had never seen before.

Again, time went by. I drove the car almost daily to soccer games, baseball games—me, my wife, and two little boys crammed in it. I took it to the supermarket, hardware store—wherever I needed to go. It sounded magnificent, with a basso profundo growl, an absolute wail at high RPM, a whining four-speed Moss gearbox, and it was painted Rolls-Royce Regal Red with a tan interior. I may have put the top up three times in the ensuing 40 years. Ferraris, Corvettes, other Jaguars, and a GNX came and went—the 120 stayed.

Three years ago, “Fred” had an unfortunate altercation with a deer. The car survived, the deer not so much. I was about to have it repaired when I was cajoled into a total cosmetic restoration. Total strip down to bare metal, new interior, re-chroming, and a mechanical freshening up. In the process, we uncovered the damage it sustained at Sebring when it took a shunt and went off course—caught on film by Ozzie Lyons! The car was as close to perfect as it was going to be, as it is a regularly driven car. Then I was talked into applying to the Amelia Island Concours. Prior to that, it took the Chief Judges Award at the Greenwich Concours.

I was shocked to be accepted at Amelia Island, and happy to tell the story of my car. I thought I had it very well documented. As a result of an interview with a British photojournalist that was put online, I received a phone call from a gentleman in Colorado. He asked me if I knew what I had? I told him yes, and then he proceeded to prove me wrong. I learned that he has a sister car—albeit one with a 9:1 compression ratio—that he has had for 48 years. The difference was that he had no documented race history or paperwork. He then put me in touch with Roger Payne in Australia who was a Jaguar historian and who, with the help of cellphone pictures of casting numbers and stampings, told me how my Jaguar came to be and what its significance is. To quote Roger’s inscription on the inside of his book, JAGUAR XK120 Authenticity Reference Guide (All Models): “What a delight to have been able to examine your very ‘special’ XK 120 S675904. This has been found to be an exceptionally rare example of a Jaguar Competitions Department race-built and prepared XK120 for a private customer, and is one of only four XK120, (sic) known to have been fitted with a ‘C’-TYPE engine as original equipment.”

Cut to the chase. Fred Dagavar was a minor racer of note with friends in the right places. He was friends with Bill France and was able to get “Lofty” England, Jaguar’s Team Manager, to have a special car built for him. Lofty was well known around the world in almost all Jaguar pits, his most valuable connection was with the Browns Lane Competition Department. Fred met Lofty at Sebring in 1953 when the Jaguar C-Types “invaded” the 12 Hours of Sebring. Lofty promised Fred he’d arrange an upgrade to his 120 in the competition department with a C-Type engine, close-ratio transmission, and other sensible modifications after Fred’s car rolled off the assembly line.

This was to be Fred’s daily driver as well as his racecar. C-Types are short on creature comforts and weather protection. Fred asked for, and had constructed, a C-Type drivetrain in a 120 open two-seater body! The head with the “sneaky valves” turned out to be a second-generation hand-tooled “C” head for the LeMans cars. The last of its kind before the “D” type head.

What is the difference? The C-Type heads had straight inlet ports, bigger valves, high contour camshaft profiles, and should move the redline from 5000 rpm to 5300 rpm. This would give at least a 20 bhp increase in engine output. Fred left the compression ratio at 8:1 as opposed to 9:1, as it was his daily driver. He did, however, order an extra set of needles for the twin SU H6 carburetors, which would provide a richer mixture at high rpm (“RB” versus standard “RG”).

According to the Jaguar Heritage Certificate, “Fred” was completed on June 25, 1954, but went back to the factory for a “factory race engined” upgrade and was not shipped until August 11—way over the average shipping time of less than a week following completion. The “all the way loose” note that I had been told to write down meant that because it was a racecar with a 13 ½ quart sump, it was engineered to burn a quart of oil every 125 miles or so, which it does. This aided cooling in endurance races.

I have had the car for 50 years, and it is only in the past few years that entire chapters of its story have surfaced. I could have lamented that Fred Dagavar didn’t buy a C-Type, especially since he was a racer. But then I found out, in his own way, he did!

'The Practical C-Type' has no comments

Be the first to comment this post!