by Graham Robson

March 15, 1961—a special date for Jaguar enthusiasts—it was the moment when the new E-Type met its public for the first time. It was the day almost every other sports car in the world suddenly looked dowdy, when Jaguar realized to their joy that they would have real problems in meeting all the orders that came flooding in. The enormous struggle to get two cars to the Geneva Motor Show had been worth it.

Of course it wasn’t easy. And those who merely bask in the theory that there had been a leisurely, well-ordered plan to bring this amazing machine to market should now think again. The fact is that it took four years to get from First Thoughts to First Deliveries. This splendid road car had started life as a racing sports car, and all manner of corners had to be cut to make it happen at all.

Let’s start with the Le Mans 24 Hour race of 1957. The Jaguar D-Type had just won this prestigious event for the third consecutive year—but the sport was in turmoil because the rules were about to change. For 1958 and beyond, the cars would have to have engines of less than 3-litres! Ferrari was delighted, but Jaguar was not. The D-Type, of course, had run 3.4 or even 3.8-litres.

Accordingly, Jaguar cancelled its ‘works’ motor racing efforts, and development of a new car got the green light. This led to what we know as the E-Type project getting under way behind the firmly closed doors of ‘Comps’ at Browns Lane, Allesley (a suburb of Coventry). Nothing about this project was yet released to the public. Work started on the design, build and initial testing of a single prototype, known as E1A. Although it was smaller and lighter than the last of the D-Types (much of the new car’s structure was in aluminium, whereas the road cars would revert to steel), it bore a striking visual resemblance to those cars, and at first only had a 2.4-litre engine. As with the D-Type before it, the styling was by Malcolm Sayer, who used closely guarded mathematics to lay out the sinuous curves.

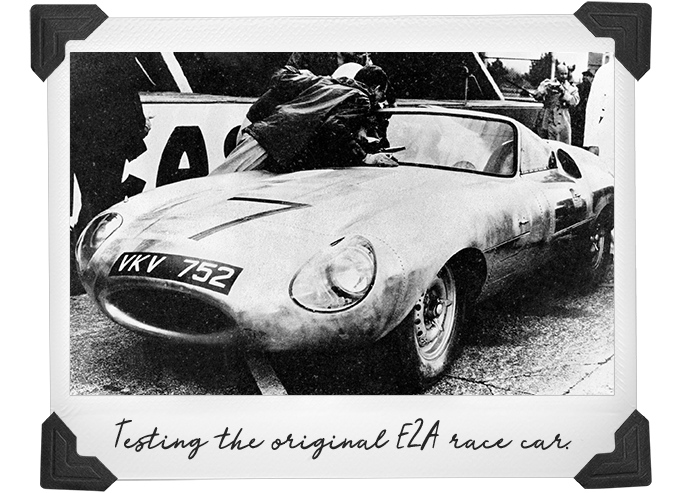

By the end of 1957 E1A, initially without headlamps, a windscreen or a registration plate, had been painted a rather insipid pale green, and chief test driver Norman Dewis began what seemed like an endless series of runs, mainly at the British motor industry’s proving ground at MIRA, a converted World War II airfield complex, close to Nuneaton, a mere ten miles north of the Jaguar factory.

Amazingly, news or photographs of this sensational car were never published even though E1A was driven on public roads to and from MIRA on each outing. Dewis made sure that he occupied what we might call ‘unsocial’ hours in making these trips—and of course in those days the specialist press was very loyal in not breaking embargoes, or publishing spy shots. Even within the factory, little was known about this new project, for every ‘Comps’ staff member and mechanic was well trained in keeping his mouth shut!

This was the time during which I was lucky enough to join Jaguar as a graduate trainee, and as I once wrote here, in Moss Motoring:

“Jaguar kitted us out with the famous apprentice-green overalls when we arrived. I was lucky, as I sometimes found time to go ‘walk-about.’ It was those strolls immediately after the canteen lunch which told me so much—for somehow the Apprentice-green kit was an acceptable disguise which were rarely challenged by officious supervisors, and it was on one of those wanderings that I first spotted the original light-green E-Type prototype on a ramp in Experimental. That was sheer happenstance, for it had recently been completed, in great secrecy in the Competition Department, which was nearby, but they didn’t have a ramp of their own. Chief test driver Norman Dewis was with the car on that day, treating it very much as his baby, which effectively it was…”

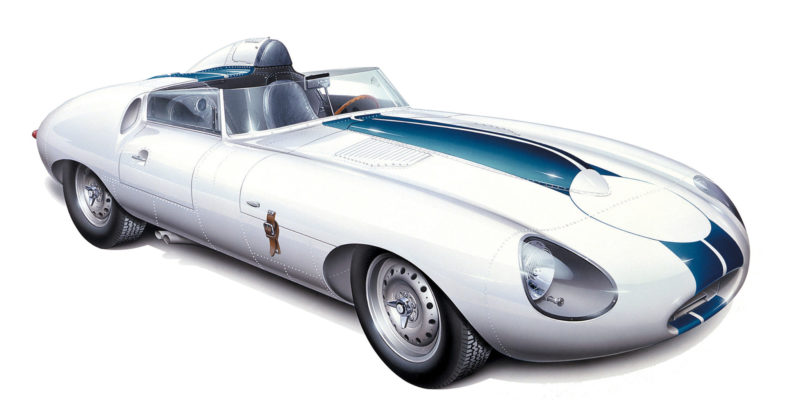

It was in 1959, by which time I had been moved into the Experimental department to learn about the way the first cars of a new range would be built, then modified, then re-built, then up-dated, then finalized (you get the picture, I hope). I realized that the E-Type project was seriously going ahead, and by the banging and sounds of activity over the partition it was clear that ‘Comps’ were building up a real E-Type race car: that machine—E2A—was unveiled in 1960, a year before the E-Type was officially revealed. It was unsuccessful at Le Mans but went on to have some race successes in the USA under Briggs Cunningham’s control.

In 1959, though, the first of the steel-bodied prototypes began to take shape in Experimental, and (from a distance) I could see what problems were clearly evolving. The basic problem was that the E-Type was going to be structurally different from the XK150 it would replace—it had a steel center/rear unit-body monocoque, allied to a multi-tube front end, instead of a separate chassis it had all-independent suspension (the XK150 had always had a beam rear axle), and it was going to need to be assembled at Browns Lane in a different way from before.

As far as I could see, the problem centered around that unit-body, for Jaguar thought it could sell at least 5,000 E-Types a year, this being a build rate they could not tackle themselves, and one that was not large enough to interest big independent body shell builders like Pressed Steel. The sensible alternative—the ‘middle ground,’ as it were—was to approach Abbey Panels, (they were located in Coventry, close to the earlier Jaguar factory which had been vacated in 1951) who had provided many of the body sections for the D-Types.

But… one hundred body shells, or part shells, every week? Could Abbey Panels cope? They could, but kept on demanding ways that assembly, or the interaction of one set of pressings with another, should be changed. Many was the time when I would see Technical Director William Heynes crawling all over the prototype, his immaculate suit gradually getting smeared, but finally getting agreement on another detail from Abbey Panels. Matters became more complicated when a fastback coupe version was proposed (this had not even been considered at first), for yet more changes were needed to the structure to cope with this.

Jaguar, though, could not deal with everything at once, for the arrival, and launch, of the new Mk II saloons took precedence in 1959. By the end of that year, too, I had been moved into the engineering design office, where I took on all manner of minor jobs—soon realizing just how much of the E-Type’s engineering had to be settled. Not only the notorious battle of Robson vs. an exhaust system layout, plus the bracketry needed to support the engine cooling fan’s electric motor—but on top of everything else, a complete check layout on drawing board paper (no computers in those days—just pencils and two dimensions) to see if the rear suspension links, driveshafts, rear anti-roll bar and exhaust pipes could all exist in the same confined space on each side of the rear axle casing!

Somehow or other, though, this fabulous new 150mph car was made ready for showing at the Geneva Motor Show, in Switzerland, where, initially, only one machine, the fast back coupe version, was originally scheduled to be on display. Because Jaguar’s budget would not hire an aircraft to fly the precious cargo all the way from Coventry (and even though there was an International airport conveniently very close to either end of the trip), it had to be driven the whole way by PR man Bobb Berry. Of course it was a cold European spring, and of course the weather was foul, but somehow the car got a thorough valet cleaning in a Geneva garage on the day before the show’s doors opened.

But there was more, and dramatically more, to come. Sir William Lyons decided that an open version of the car should immediately be sent to Geneva and—because nothing was impossible to Sir William—he demanded that this be delivered overnight. Test driver Norman Dewis had no option but to ‘do his Superman bit’ (as he once told me, in later life) and once reported that: “They asked me to leave the factory and drive direct to Geneva. I had a nice trouble-free run and achieved a very high average speed.”

That, in fact, was a typical understated British way of describing an overnight dash, which started in Coventry at 4pm one afternoon, and an arrival in Geneva at breakfast time the following morning. Oh, and by the way, the distance between the two cities was 730 miles, the trip was overnight, Norman was by himself, there were very few freeways in those days, and there were two border crossings to negotiate, and a 90-minute cross-Channel ferry trip to factor in to

this scramble.

And so it was. The launch of the new E-Type was a huge success, the first orders flooded in, and Abbey Panels, in particular just, and only just, had time to take a deep breath before starting to build bodies in numbers. In fact the archive shows that only 16 cars were built in March 1961, a mere eight followed in April, twenty-one in May, and 109 in June.

But the job had been done, and Jaguar’s designers immediately settled down to working the same miracle on another new car, which, by complete contrast, was the massive Mk X saloon.MM

'The Origin of the Legendary E-Type, 60 Years in the Making' has no comments

Be the first to comment this post!