by the late Graham Robson

Before Graham passed away last year he asked what topics I wanted him to write about for Moss Motoring. So often he wrote about leaders who influenced the British car industry, but my favorite stories of his were when he gave readers a look into highlights of his own life with cars. With that as my request, the following story landed on my desk not long after. Graham clearly enjoyed the assignment. I wish I would have asked earlier for more stories like this.

- David Stuursma, editor

My other name is Walter Mitty. No, hang on, what I really mean is there have been occasions, too few to be complacent about, when I felt like Walter Mitty. Sometimes, just sometimes, I have driven special cars, in special places, on special assignments. This, involving an MGB Le Mans race car, was one of them. It’s true, and somewhere in the British Autocar magazine archives, impenetrably hidden away, there are pictures to prove it.

It was a hot summer week in Britain, in July 1965, when the place was boiling with tourists. There were no maximum speed limits on our roads, and as a young journalist I was still crazy enough to find most impossible things quite possible.

There I was, halfway around London’s Hyde Park Corner in a Friday afternoon traffic jam, with a Routemaster bus on my left, and a line of black taxi cabs on my right. You haven’t been to London maybe—so I’ll just compare it with the maelstrom of Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue. So why was I, right then and there, in a brightly liveried red MGB with a white hardtop, which just happened to be carrying the huge competition number 39 on each door, seemed to have no muffler—or at least, the one which was fitted must have blown out its fillings some days ago—was registered DRX 255C in Oxford, and was fitted with that iconic, arguably unique, lengthened Le Mans nose? Just in case I was worried about nudging one of those aggressive “I’ve got rights” black cabs, I also had to remember that this car had no bumpers, and that there were two extra Lucas driving lamps mounted up front, too.

It was a hot day, I knew that this machine stood out from the usual automotive crowds which were thronging London’s streets at the time, and I knew that I would still have to endure 30 minutes, and miles of suburban rough-and-tumble in north London, before reaching the southern tip of the M1 which pointed to Coventry and the north.

This was all a rather stressful dream, right? The sort of fantasy motoring affair where the most remarkable things happen—until you waken up, and spend the rest of night wishing that it were so? Except that on this occasion it was all very real. It was July 1965, and I really was driving the self-same ‘works’ MGB in which Paddy Hopkirk and Andrew Hedges had just finished 11th at Le Mans, averaging 98mph. Incidentally, scrabbling away behind all the Ferraris and Porsches which were ahead of it in the French 24-hour race, it was the first finisher to look anything like a road car that a spectator might, one day, own.

Somehow, though, I made it—waving at Regent’s Park as I passed it on my right, and the Lords cricket ground (the “Home of Cricket”) on the left, before things got less frantic after I reached M1, especially as those were the days before the 70mph speed limit had been imposed, so I didn’t have to keep a look-out for the blue flashing lights, which would certainly have ruined my day.

It didn’t help, of course, that this was a car that had just finished the Le Mans race itself, the 1.8-litre engine surely needed a bit of loving care, and it was also clear that the clutch (in-out, no half-way house) was past its best. Fear not—by the time I got home to Kenilworth (south of Coventry) I was feeling quite cocky about the whole business. Not many people that I knew ever got a chance to arrive home, in suburbia, in a recognizable racer. And how often was someone else paying for it all? These were the happy days, too, when I felt secure enough to leave the car parked outside overnight.

It had happened like this. Having recently joined Autocar, theoretically as a road tester, and as their resident “rally man,” but working out of a satellite office in Coventry, close to the MIRA proving grounds, I already knew my way round all the works competition departments of the day and—I hoped—was already treated as credible, and as someone who might be trusted not to crash irreplaceable competition cars. Even so, it was a real surprise to discover that BMC’s Competitions Press Officer, Wilson McComb, came back from the 1965 Le Mans race, decided to unleash DRX 255C on the press, and called us:

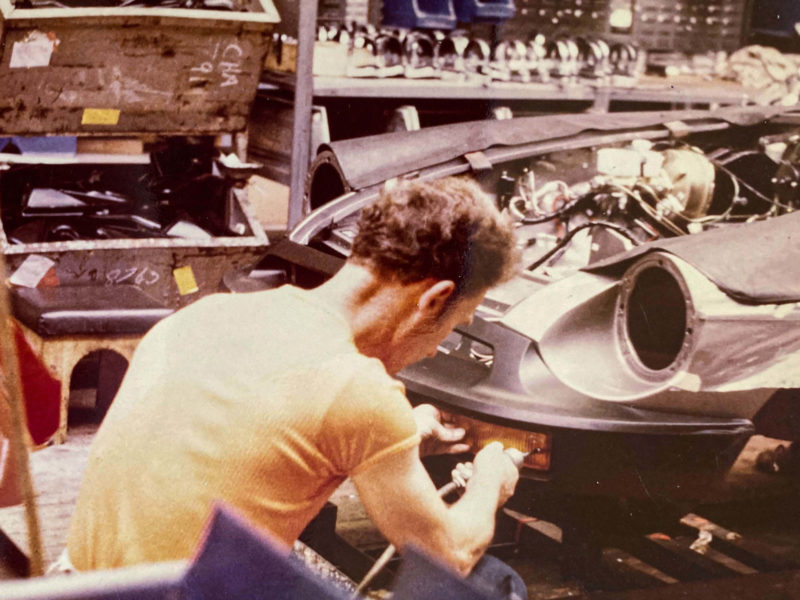

“Would you like to try out the Le Mans MGB? You can have it for about a week,” he said, “but remember that we really haven’t had time to give it more than a good clean since the race, and to put the axle ratio back from its Le Mans 3.04:1 to 4.55:1. It’s licenced and road legal—but try not to break it—we might need it to race again quite soon!”

Technical Editor Geoffrey Howard pulled rank by getting his hands on it first, basing it at Autocar’s London HQ, on the south bank of the Thames, near Waterloo station, but as it then had to be driven to MIRA (the industry’s proving ground, near Nuneaton) for performance figures to be taken, therefore (and, well, let’s be honest, I didn’t need any other excuses) I was obliged to do the 100-mile commute from there.

There were, to be honest, some good points—and some bad. Posing about in a genuine Le Mans car was enough to tip every balance, especially as this MGB had the factory’s 3-main-bearing 125bhp Stage 6 engine tune (which included a single twin-choke Weber carburettor, and a special exhaust manifold), the optional close-ratio gearbox, 5.5-inch wire-spoke wheels, and Dunlop R6 racing tyres, along with an extra fuel tank (bringing the total to 20.5 gallons), and that unique droop-snoot nose. Was it road-legal in that form? I was never sure, but I am certain that any traffic policemen would have looked kindly the other way if the need arose.

There was, however, one definite let-down which, as my colleague Howard later wrote about firing up the engine from cold:

“Suddenly, after a few grinding turns [of the starter motor] a deafening roar breaks out as the engine comes to life: it may have started the race with stuffing in the silencer, but now there’s a completely un-muffled window-shattering snarl bordering on the threshold of pain. Within a few miles we’re getting along nicely without disturbing too many people. Feather-foot it in towns, and look helpless and embarrassed when people turn and glare, is the knack to be learned early on. There’s no fan so any delayed traffic stop means switching off to prevent the engine temperature soaring.”

I can back up all of this by noting that one evening during the following week, my wife and I went out to dinner, 40 miles away, with friends, knowing that we would have to start up this precious car at about 11pm to go home, when their neighbors were on the way to bed. Fortunately, my friends knew all about my profession, and were used to seeing me turn up in some strange machines. Even so, when we arrived, with me still quivering with joy at the journey I had just completed, the wine was already on the table. They assured us that they knew we were about to arrive when we were still well up the road, and that, yes, they would have a placatory word with their neighbors in the morning . My wife also complained that she was uncomfortable in the lightweight (i.e., unpadded) passenger seat, and commented that there was really rather a lot of heat permeating through the floor, above the muffler. She was, mind you, an extremely understanding lady—for there was another occasion when I brought a road-equipped Ford GT40 home for the night, and she insisted that we both went out to do some shopping in it.

Incidentally, I should add that at MIRA we found time to assess the race-car handling characteristics, and enjoyed it, as well as recording a top speed (with that very short 4.55:1 rear axle ratio) of only 105mph, though 0-60mph in 8.2sec, and 0-100mph in 25.0sec brought smiles to our faces too. If it had retained its Le Mans axle ratio for our trial, that would have meant using a first gear which was good for more than 60mph before an up-change was needed.

Nearly sixty years on, by the way, that particular car (which was sold off to an MGCC stalwart after its long-nose body style had been removed) is still alive, still in well-loved and well-maintained racing tune, and appears regularly on the MG scene in Britain. And every time I see it, I pat it lovingly, reminding myself of a fabulous experience. MM

'The Le Mans MGB in Traffic' has no comments

Be the first to comment this post!