by Pat Sykora, aka “The Bird,” with technical input from Ernie Connor

The sound was unmistakable. No need to look to know that the miserable, hot, sweaty hours of finger-numbing work were over. The nanosecond of verbal restraint followed by an oath akin to “bugger,” belied the cold, hard truth: I cracked the bleeping windscreen.

It wasn’t the first, nor would it be the last, in a string of setbacks as I approached the finish line of my four and a half year restoration of a 1960 Austin-Healey Sprite. Anyone who has ever endeavored to restore a car knows the process can be described in many ways, but the image that prevailed for me in the final months was that of being in the Red Zone: the goal in sight, but those last yards…

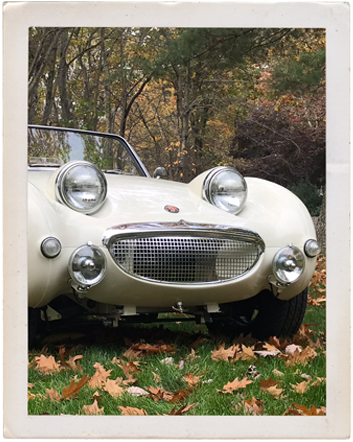

It began in 2016 with an eBay ad, a phone call, a tech session, and a friend saying, “You want it? Buy it!” The next weekend my son and I were on our way to Connecticut with a pocketful of cash and a borrowed truck and trailer to bring the Bugeye to Rhode Island. The “easy part” started in earnest. The stripped, rusty carcass was put on a homemade rotisserie and things were cooking with an ambitious initial estimated finish time of two years.

Two years later, it was far from complete. The problem, if it is a problem, is that I’ve been told I don’t play nicely with others. Whether this is true or not, it has been noted that I prefer to do all aspects of a restoration myself, and others have wisely intuited that it is best to keep their distance unless invited to my sandbox. As with many restorers, this is my “hobby,” and, as such, a “challenging learning process” that is best endeavored without people you want to keep in your circle of friends. Aforementioned optimistic estimate aside, I now believe that timelines are best laughed at derisively and disregarded, if for no other reason than to keep scoffers at bay. Yet, I had made quite a bit of forward progress: the tub was repaired and primed, my redesigned and self-fabricated wiring harness installed along with the engine and restored running gear. The Bugeye, now named “IV” (Ivy), as she is my fourth Brit, was drivable. But this was only the first half of the game.

The second half began with rebuilding and upholstering the seats and dash. This proved strategically brilliant as it provided a refuge in the upstairs storage area during countless moments of despair. Gazing at the shiny chrome dials and plump bolsters was sweet respite from what awaited in the garage—my most formidable opponent, the bonnet. Devoid of the eyes and bright smile that makes a Bugeye look jolly, it was a sneering red chunk straight from hell. After removing pounds of Bondo, previous repairs that seemed to have been done in a High School Vo-tech shop mocked me. I should have returned to eBay to find another, but kept telling myself that if I cut, welded, shrunk, hammered, and dollied enough I could make a purse from the sow’s ear. Over a year later, I was looking online regularly and unsuccessfully for better options. It was fourth quarter and I would go with the players I had on the field.

The finishing touches were done, and the bonnet and tub were primed and prepped for paint. Fortunately, the pandemic had cut back drastically on other things I might have been doing like trips, golf, lunch, and dinner dates—life in general. I forgot the folly of schedules, and set my sights on the rescheduled Bristol, Rhode Island British car show. Perhaps even the British Invasion in Stowe, Vermont.

It was a given that I would paint IV in my garage. Previous experience with my Spitfire predicted a high chance of success. After spraying and sanding and sanding and sanding and sanding, came the buffing and buffing and… you get the picture. Perhaps, it was time I should learn to play nicely with my significant other. My “bird,” who was getting strangely jealous and about to get back on Match.com, was recruited as an apprentice for this and other upcoming pieces of the project. If nothing else, we could pretend we were on a date during the pandemic.

I was the one who sanded through to the primer. The touch-up with leftover paint was, no surprise, an epic failure. Another trip to the paint supplier and this “Old English white guy” had a color match, resprayed the right front wing and the boot, and started sanding and sanding and sanding. My apprentice, no longer jealous, decided pruning shrubs was the better option.

There is something about attaching the windscreen that brings the goal line into focus. After watching a couple YouTube videos that made it look easy, we wrestled with gaskets and glass, used enough lube to host an oil wrestling event, uttered many unprintable words, ruined three or four old hotel key cards, and I sunk to the concrete exhausted when the glass finally popped into the frame over two hours later. We called it a day and headed for the Pandemic Pub (my refrigerator). The next weekend was bloody hot, but it was either install the windscreen or trim more hedges. In retrospect, we should have done the latter. Kindly return to the opening paragraph of this saga.

Two weeks later, with the help of two $3 tools, which would prove their worth over and over, the second windscreen and gasket came together “Bob’s your uncle” and, feeling on a roll, we dove right into the install. We reviewed what NOT to do and labored in fearful silence until all four bolts were in and all four hands lifted cautiously away. Rejoicing was short-lived as our eyes were drawn down to a glaring gap between the gasket and the cowl. Another online survey revealed that, while this imperfection is common, IV’s gap was uncommonly large. Once again cursing British engineering, the only option was to remove the windscreen and reform the cowl. This involved partially dismantling the dash, a chunk of wood and a small hydraulic jack. It was undeniably crude, but it worked well enough. The windscreen was attached for a third time, the wipers reattached and tested. Of course they didn’t work. We called it another day and headed back to the ever-popular Pandemic Pub. A defective wheel box would be my project a couple days later.

The Red Zone is a perilous place. Sanded through paint, broken windscreens, funky cowl, defective wheel boxes… So close, and yet, so far. I was certain I had done everything twice. I turned my focus back to shiny objects—new alloy wheels—and called to schedule the tire install and balance. I arrived on the appointed day only to be given a large helping of “nope” on the install of new tires on after-market wheels. A different local tire shop came to the rescue, but upon mounting the first wheel, the balancing weights got knocked off by the tie rod end. I have become a well-known repeat customer in supply and service shops around Rhode Island.

The last phase, putting all the pretty bits together, is the final pass into the end zone. As the tub was transformed by soundproofing, carpet, panels, seats and a truly “proper” steering wheel, all the dropped passes and fumbles faded into history. It took one more morning to attach and tweak the bonnet and IV was ready for her maiden voyage around the neighborhood. It had been four years and 151 days since the trip to Connecticut. Thumbs up from neighbors assured me that my smiling Bugeye puts to shame the growling Camaro four houses down. Of course, each drive I take creates a punch list of things to sharpen up. A restoration is the gift that just keeps giving.

If you are reading this, you are already vested in some way in this great hobby. If you have done or are doing a restoration, I hope my story resonates with your own experience and makes you smile. If you are new to ownership of a vintage British motorcar or yet to engage in a restoration, I share all this not to discourage—quite the opposite actually. I believe it is all the setbacks and successes that make each and every ride so very gratifying and such a source of pride. The intimacy between us and our machines is enhanced by knowing every bit of them from the rubber on the pavement up. Restoration is the work of craftsmen—men and women put head, hands and heart into the process of creating or recreating something beautiful. Whether you drive a Rolls or a Mini, restore by yourself, play well with others, or buy at the auctions, you are part of a game well worth showing up for—continuing and preserving passion for vintage British sports cars. MM

'The Red Zone' has 1 comment

January 21, 2022 @ 7:02 pm Paul Graham

Much thanks to Pat. The article was an epiphany. ” The problem, if it is a problem, is that I’ve been told I don’t play nicely with others. Whether this is true or not, it has been noted that I prefer to do all aspects of a restoration myself, and others have wisely intuited that it is best to keep their distance unless invited to my sandbox. As with many restorers, this is my “hobby,” and, as such, a “challenging learning process” that is best endeavored without people you want to keep in your circle of friends. Aforementioned optimistic estimate aside, I now believe that timelines are best laughed at derisively and disregarded, if for no other reason than to keep scoffers at bay.” Describes my multiple MGB project(s) to a tee. The LBC habit turns fifty this year.