by Bruce Porter

The Trials of Driving a Morgan That Would Rather Have Stayed Home in Britain

The plan was to pick up the brand new 1986 Morgan Plus 8 in San Francisco, where it was imported from the factory in England, and drive it back home to Brooklyn. I’d been warned, of course, that taking it on a 3,000-mile trip was an experience not even Morgan zealots would anticipate with much joy. Its steering is stiff to the extent that wrenching the car around curves feels a little like doing weight training arm exercises. There’s no insulation in the firewall, which means that heat from the engine compartment pours onto one’s feet in nearly visible waves. Then there’s the famous Morgan ride, about which the standard joke—that the car hits the first and fourth bumps, hurtling over the middle two—only mildly overstates the case. On top of all this, the car’s engine—a monster 3.5-liter V-8 from Rover that can push it up to 150 miles an hour—is routinely converted by the lone US dealer to run on propane instead of gasoline in order to satisfy American clean air standards. “Where on earth will you get propane?” friends asked. “No problem, it’s everywhere,” I said. “I’ve got a book.”

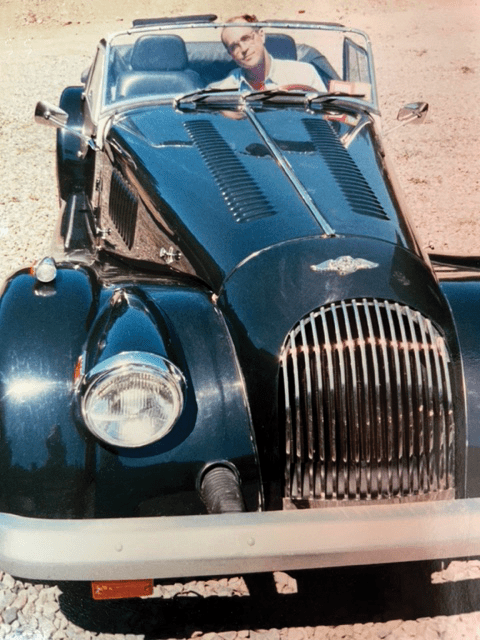

Whatever secret qualms I had melted away when I arrived in San Francisco and saw the car sitting with the top down on Pier 33, its low, sinuous, roadster shape outlined against the harbor, its color a deep, deep, almost black green—a machine that could be described as achingly beautiful. “A little champagne before setting out?” the dealer asked as he brought out a couple of glasses.

Soon l was hurtling out of San Francisco down U.S. 101, past those grassy hills that look like the backs of golden bears, one arm draped over the gentle dip in the door. At Palo Alto I picked up a friend, Wade Greene, who had flown out from New York on business and would ride back with me as far as Santa Fe. A Lincoln Continental pulled up at a light. “That one of those plastic replica cars?” asked a voice from within. I looked over blankly and depressed the accelerator. A noise like that of a small earth tremor emerged from the twin exhausts. “Oh,” said the voice. I moved off.

San Jose, 5pm. Horrendous traffic jam. Also very hot, the Morgan not happy. Its home in Malvern, England, sits on the same latitude as Labrador, Canada; where it is now lies in the Mediterranean. Wade is marveling at the amount of heat being experienced by his feet. Anxiety about the radiator’s boiling over dominates the conversation, until our attention is diverted at a stop light by the fact that the gear shift seems to have come off in my hand.

Instant depression. It is Friday evening, the start of Memorial Day weekend, in the leisure capital of the world where the chance of finding anyone to work on a broken Morgan gear shift is about the same as the car’s sprouting wings. We haul our depression into the cool recesses of El Rancho Bar in a shopping mall across the street. The Morgan will just have to be flat-bedded back to San Francisco. We’ll fly home. Forget the whole trip. Great! Our predicament makes the rounds of the bar to the general heehawing of men and women in cowboy hats. You boys driving to New York? Car runs on propane? Everybody goes out to have a look. There we find a young man affixing his business card to our windshield. “What’s the trouble?” he asks. “I saw it was a Morgan: I had to stop.” Turns out he runs a garage that specializes in British cars. Quickly he unfastens the gear box. “Nothing serious,” he says. “A screw has come loose, that’s all. Get the car towed to my house, take about 30 seconds to fix.” (Not counting, as it turns out, the six hours it takes him to tear down the gear box to get at the screw.)

Nevertheless, Saturday we’re back on the road, zooming through the San Joaquin Valley, past the giant rolling irrigators that make the desert bloom. After a stop at a friend’s in Hollywood for a swim and a bed, we set out to cross the Mojave Desert. In late May and without air-conditioning, this is something to be undertaken at night, listening to the tires crunching the tarantulas that lie on the road. We’re in a hurry; so after filling up with propane at an RV campsite near Barstow, a desolate, treeless place that fits our image of a penal colony in the sub-Sahara, we hit the worst stretch of the desert at about noon, with 200 miles to go.

It is 110 degrees. We have put up the top but the waves of heat pouring in through the sides and through the firewall from the engine make it feel as if we’d left the oven on broil for 24 hours and then climbed inside. The Morgan is seriously hyperthermic, its temperature needle lying close to the pin that signals 140 degrees Centigrade. Nothing around but sand, scrub and cactus. It now dawns on us why Indians in the Southwest stand in clutches under road signs—crowding into that little parallelogram of shade. Greene notices that the wiper blades are melting onto the windshield. Finally, thankfully, we reach Needles, stop the car and hurl our bodies into the Colorado River.

From the low desert at Needles, the road climbs a cooling 8,000 feet to Santa Fe, whence Greene flies home, and another friend, Tad White, a New York admiralty lawyer, takes his seat. By now we’d gotten the hang of finding fuel at various propane wholesalers, truck stops and campgrounds to the extent that we’d stopped thinking of ourselves as desperate characters out of “Road Warriors.” The only real worry is running dry at night, a fear that toward 5 P.M. forces us into 100-mile-an-hour dashes to catch a propane place before it closes.

According to a billboard outside Liberal, Kansas, this is where Dorothy lived before being tornadoed to Oz, something that encouraged local boosters to bill the town as “The Land of Ahhhs.” It is also the center for the formidable Kansas thunderstorm, which can arise in minutes and meeting no resistance from the prairie, build to an intensity rarely known in the East or West.

We ran into a sample halfway between Liberal and Wichita, when a malignant, gun-metal gray curtain suddenly dropped down all across the horizon. As we rushed to get the top up, raindrops with enough water to fill a shot glass began splashing on the car; within seconds we were driving through a waterfall, the tiny Morgan windshield wipers unable to cope. The wind picked up. Then hailstones the size of cherries started banging down, and the storm clawed open all the imperfections and pores in the Morgan top, which is not made to withstand anything more formidable than Scotch mist. In no time, we were drenched as well as driving blind, 18-wheelers swooshing by. Finally, an overpass loomed ahead, and we pulled over to wait out the deluge.

From St. Louis on, I drove alone, barreling along Interstate 70, wanting badly to get home. Illinois, Indiana, Ohio just a blur. Bolts began coming loose in the undercarriage, the British apparently not having discovered lock washers, and when the car hit northern Pennsylvania, it began having serious problems with the rotten roads of the frost belt. Its rear suspension consists of a 100-pound axle and a couple of leaf springs, about as sophisticated a mechanism as on, say, a manure spreader. With not much to dampen it, when the car encounters a major bump the rear end takes off into space. The driver’s knees crash into the underside of the dashboard and his head strikes the strut holding up the top. The trick is to avoid bumps.

A brief stop at Gettysburg to see the Peach Orchard, where my great-grandfather, Isaac Porter, lost his arm during the battle. Then there I was crossing the Verrazano Bridge and too suddenly bouncing over the decrepit streets of Brooklyn, feeling slightly out of place, the car begging to be put back on a smooth highway, and among the many reflections I was having about the eight-day trip was how to tell Wade Green that I’d misread the instructions for a switch under the dashboard and we’d had the heater running full blast all across the Mojave.

Looking Back

I fell for the Plus 8 in the summer of 1985. A magazine had sent me to the UK to do a story about Peter Morgan and his son Charles, whose family had been famously building the car since 1909, and at the same factory near the Welsh border. I watched workmen push a new model off the assembly line, a vision I challenge anyone to resist emptying their IRA account for, along with their child’s college fund, so as to take possession immediately of this irresistible vehicle.

That decision prompted my eight-day cross-country odyssey a year later to bring the lady home—a story I shared in the New York Times. In those days all new Morgans had to be converted from gasoline to propane to pass US emission standards. This nod to a safer environment caused major obstacles when taking it on the road. Not only were propane dealers lamentably scarce, and located well off our route home, but they harbored this apprehension that, once the car had taken on 20 gallons of their super-volatile motor fuel, it awaited only activation of the starter switch to blow itself sky-high.

On the other hand, there’s almost no hardship I wouldn’t gladly endure while driving a British sports car—for a little while, at any rate. Unfortunately, being 6-foot-3, I never quite fit into any of them, including a rickety and abused MGTD and a down-on-its-luck TR3B.

My last year of Morgan ownership was 2008. I had turned 70, newly retired as a professor at the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism. I drove it down from Gloucester, Mass, to our place in Greenwich Village. It was 104 degrees; I had the top up and the side curtains off, to blow in some air. Arriving in the city after five hours of heavy traffic, I was so overwhelmed by the engine heat and this feeling of disorientation that I could hardly pry myself out of the car. That did it. I sold the Morgan for an old duffer’s sports car, which was an air conditioned 1989 Mercedes 560 SL hardtop convertible, jet black, the last year they made it. I found it where many end up as their final resting place, an old Mercedes dealership in Pompano Beach, Florida.

Ah comfort. Ah peace.

But what fun it had been.

'Bouncing Across America' has 1 comment

October 7, 2023 @ 7:50 am Jack Diehl

Thanks for such a well written and thoroughly entertaining article.